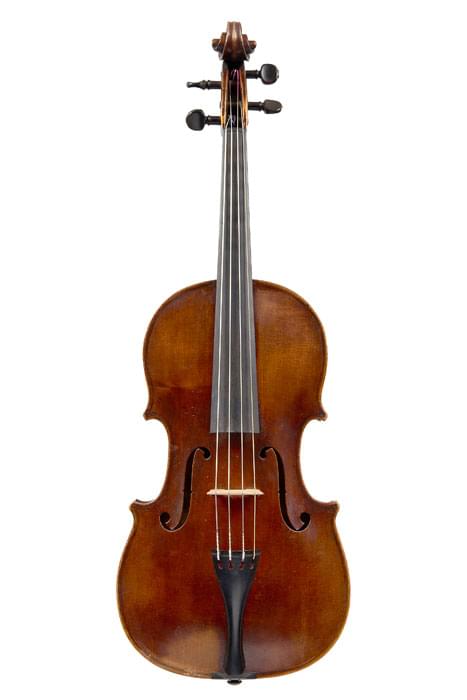

A fine viola by Giovanni Battista Guadagnini, 1779

John Dilworth discusses the work of a master.

Giovanni Battista Guadagnini’s work is full of surprises, sudden changes of direction and inspiration. From what we think we know of him via the writing of Cozio di Salabue, he was a stubborn, awkward and possibly arrogant individual. But there is a very different interpretation available from looking at his instruments. From Duane Rosengard’s biography of 2000, there is a strong sense of a self-made man, the son of a farmer who somehow taught himself the skills of a violin maker, and sought out the guidance and help of musicians as well as wealthy patrons.

When Cozio encountered him at the end of his life in Turin, he was a grand old man of violin making, the last survivor of a classical age – a fact that the young and enthusiastic Count was perceptively aware of. The Count was keen to mould Guadagnini into a more conventional Stradivarian, and offered him an exclusive contract to make instruments for him. In a strictly commercial way, Cozio obviously wished to promote Guadagnini as a second Stradivari, his pupil and natural successor, and for that to work, his instruments needed to look more Stradivarian than they had before. So poor old Guadagnini found himself being manipulated by the less than 20 year old aristocrat.

He had experience of the patriarchal classes. In Parma he worked for the Marquis du Tillot, minister to the Bourbon King Don Felipe. He adopted the motto ‘Serviens C.S.R.’ (an acronym for Celsitudinis Suae Realis, ‘in the service of his Majesty’) on his label. But patronage is a fragile thing. When the king died, cuts were introduced across the court, du Tillot was out of favour, and Guadagnini was out on a limb. This, and possibly a connection with Gaetano Pugnani, the great Torinese violinist, brought him to Turin and his meeting with Cozio, with whom he might well have been very cautious.

'Another theme runs through Guadagnini’s peregrinatory career however, and that is his very strong and clear relationship with professional musicians.'

Another theme runs through Guadagnini’s peregrinatory career however, and that is his very strong and clear relationship with professional musicians. Rosengard narrates his relationship with the Ferrari brothers. They were close contemporaries of Guadagnini’s, and knew him in Piacenza. Paolo Ferrari was a violinist and violist, Carlo a cellist. I have no doubt that these musicians guided Giovanni Battista very closely in determining the form and sound of his instruments, and provided the very individual approach to sound production as well as general form that is evident in all his work.

Carlo preceded Guadagnini to Milan, and both brothers entered the service of the Duke of Parma, which precipitated his move to that city in 1758. All through Guadagnini’s career in Piacenza, Milan and Parma, his constant shifting of proportions and archings, (especially in his quite revolutionary approach to the cello, which he developed into a very ‘streamlined’ compact model that is a delight for soloists to manage), and also his succession of very short violas, plainly built with the dual role of violinist/violist in mind, would seem to be led by the demands of the player in terms of comfort and performance.

Which brings us to Turin at last, to which he may have been drawn by the great violinist Gaetano Pugnani, and this 1779 viola which is a quite spectacular early example of the turbulent relationship between Cozio and Guadagnini, and what we might call today a ‘makeover’, or more to the point a ‘rebranding excercise’. On the label Guadagnini proclaims himself ‘Cremonensis’; a title only vaguely correct even at the furthest stretch. Later would come labels in which he actually claimed to be ‘alumnus Antonio Stradivari’. But in making this viola, you can almost hear Guadagnini saying ‘you want a Stradivari? I’ll make you a Stradivari you never saw before!’ It is an amazing departure from his previous work, abandoning the almost over-ripe elegance of his Parma style for a robust, muscular caricature of Stradivari’s own late period.

'This 1779 viola…is a quite spectacular early example of the turbulent relationship between Cozio and Guadagnini.'

The model is quite consistent with other late violas, in measurement very close indeed to the ‘Cozio’ of 1773, the ‘Wurlitzer’ of 1780 and ‘Decima’ of 1783. It has unfortunately been shortened very slightly at each end by a total of approximately 6mm, but the original edges have been retained, and in all other ways is outstandingly well preserved. Quite why this adjustment was thought necessary is a mystery, but we can be grateful it was done sensitively.

The powerful aspect of the instrument comes from the full arching; although reasonably low, it sustains a full convex curve in all directions. There is no edge flute at all, even though the edge is perfectly preserved with no wear or damage. Even in the corners, the arch still rises from the purfling, and only the slightest token sweep of a gouge spoons out the very end of the purfling mitre to define the corner.

On the front, Guadagnini has cut great, broad soundholes in very Stradivarian style, complete with wide, fluted lower wings, and circular finials – or nearly circular, since they are hand cut, not drilled in Cremonese fashion. The fluting extends towards the edge, and here in the middle bouts of the front is the only trace of a channel over the purfling. The head too is massive, emphasised by the thick black painted chamfer, another obvious nod towards Stradivari, but the workmanship is ferociously idiosyncratic.

'It is an amazing departure from his previous work, abandoning the almost over-ripe elegance of his Parma style for a robust, muscular caricature of Stradivari’s own late period.'

The varnish is also quite a departure for Guadagnini; thick, dark and profusely crackled, it appears to be rubbed quite strongly into the wood, yet has quite a strong thickness, and is present in a virtually complete and undiminished coating.

The wood it covers is not the greatest. Guadagnini used a great deal of locally sourced field maple or ‘oppio’. Even though under the terms of the contact made with Cozio, the Count was to pay for all the materials used, very little imported ‘classical’ figured maple is to be found in any of Guadagnini’s numerous Turin works. There is a charming paragraph in Cozio’s notes where he recommends for ‘domestic maple there is Varini who is a dealer in wood for furniture near the parish church in the main square’. Perhaps Varini supplied the wood for this viola, which is cut on the half slab, and the normally deeply contrasting narrow figure characteristic of oppio is softened out. Quarter cut oppio is used on the ribs, the scroll is of plain maple, and the front is of conventional spruce, of straight and narrow grain.

Guadagnini was prolific in his last years in Turin. He was 60 when he arrived there, and about 65 when he made this viola. He continued working until his death in 1786, not only making instruments but carrying out all sorts of repairs for Cozio and others. In his letters he repeatedly asks Cozio for payment; there was no hope of an easy retirement. His work there is characteristically quick and rugged, but still full of vigour and passion to the very end.

Outlived by his last mentor and patron, Count Cozio, Guadagnini nevertheless left one of the longest dynasties in Italian lutherie, extending into the middle of the twentieth century in Turin, and of course a wonderful legacy of the most idiosyncratic, intriguing and beautifully voiced instruments.

'Guadagnini was prolific in his last years in Turin. He was 60 when he arrived there, and about 65 when he made this viola.'

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani, Mathias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (5)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (4)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (2)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (9)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (2)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)