‘Ex-Corbett; ex-Bennett’ Girolamo Amati II violin

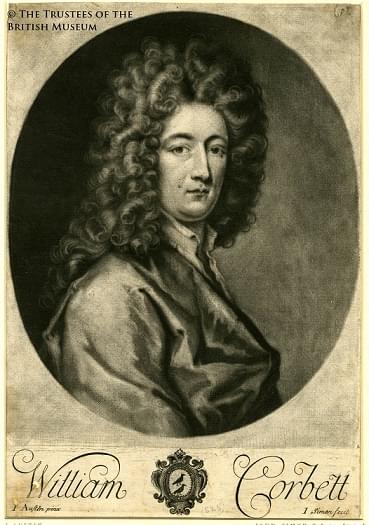

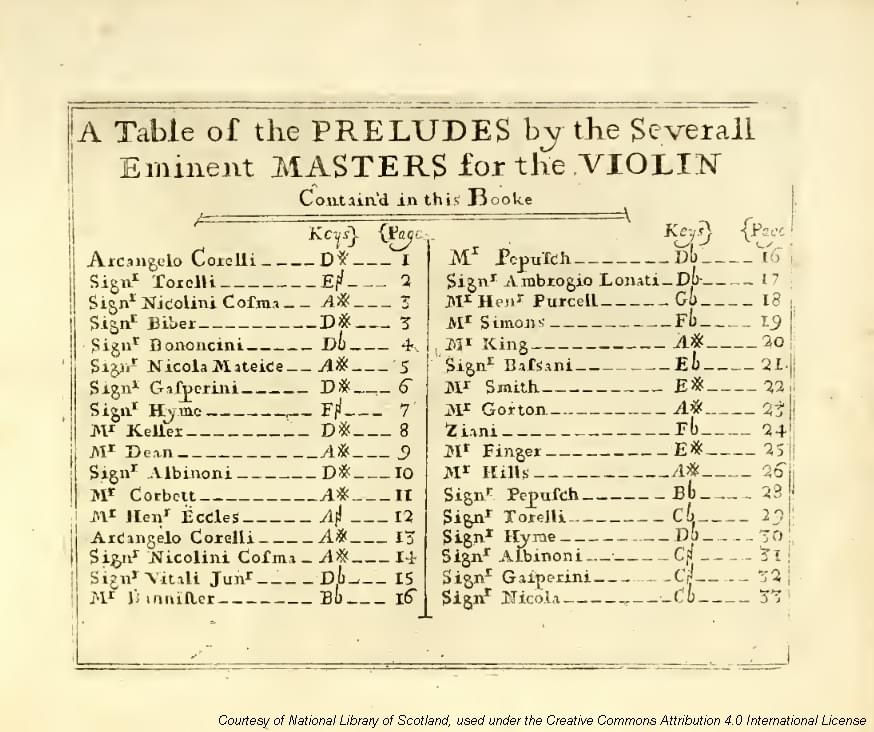

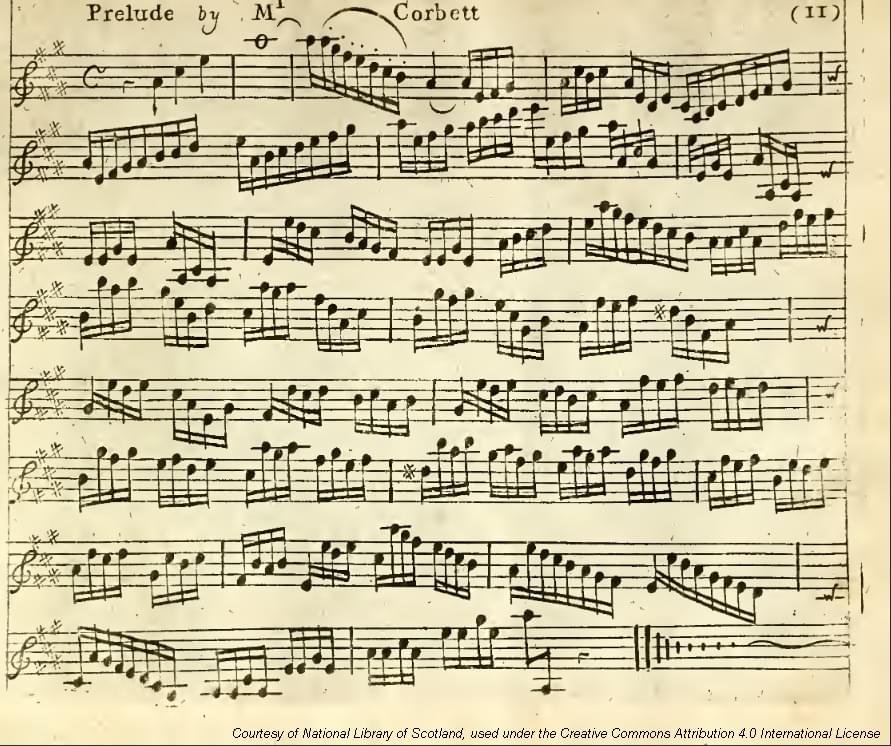

William Corbett came to prominence as a violinist and composer at the end of the 1690s, predominantly working at the theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where he composed incidental music in 1700 for Betterton’s “Love Betrayed” and various other dramatic works, including a succession of adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays. His particular importance as a composer rests largely on his success as an Englishman writing in the most modern Italian styles, and in 1700 he sent his XII Sonate a Tre to Amsterdam to be published as a response to the popular success of Corelli’s sonatas that had been widely disseminated in the preceding decade, forming the backbone of musical taste for the violin throughout Europe. As such, Corbett seems to have been something of a phenomenon, with concerts in the early years of the 18th century where celebrated Italian violinists would play his works, and his own acceptance as one of very few English musicians who were seen on equal terms to his Italian peers both in London and in his later tours in Italy. He was thoroughly integrated into the Italian musical community in London and in 1703 he married Signora Anna Lodi, a tempestuous opera singer from Milan. In 1705, when the Queen’s Theatre was opened in the Haymarket with Italian opera at its heart, he became the leader of the orchestra, and in 1709 Queen Anne appointed him to a place as a Royal Musician, a position that he maintained for the rest of his life despite his frequent and mysterious absences from England.

From the outset of Corelli’s fame, the English had been keen to induce the composer to come to London, something he refused because he had taken Holy Orders in the Catholic Church, preventing him coming to a Protestant country. The result of this had been for a succession of his pupils to travel to London in his place. Hence the Duke of Bedford was able to bring Corelli’s best pupil, Nicolo Cosimi, to London in 1702, and Cosimi in turn seems to have some responsibility for nurturing Corbett’s passion for collecting violins. As an inveterate violin dealer, his notebooks in 1702 record the £7, 6 shillings received from Mr Auden “for the Mattio Albo violin I brought to him from Rome.” Albanis were clearly the rage in Cosimi’s circle, for he took a “mediocre Albo” in part exchange for lessons in 1703, selling it the following year for an astonishing 18 guineas. Amongst Corbett’s collection of violins were two Albani violins from the year 1683, one that belonged to Cosimi and the other to Corelli.

'Corbett’s purpose in Italy provided the perfect cover for espionage.'

Perhaps more influential to Corbett was the Cremonese nobleman Gaspar Visconti who arrived in 1703 in England as another pupil of Corelli, and with whom he regularly performed. In March 1704 Corbett put together a ‘benefit concert’ including Visconti, James Paisible and John Banister (II) at the fashionable York Buildings, and in a benefit for Giuseppe Olzi in April, Visconti performed Corbett’s sonatas. He returned to Cremona in 1705 having married Christina Stefkins, the daughter of another celebrated musician in royal service in the English court. In turn, Visconti certainly knew Stradivari, for surviving templates indicate that he made a viola da gamba for Christina, and in 1720 the biographer Dom Desidero Arisi touched upon the idea that Visconti was the musician who assisted Stradivari in his designs. It is worth mentioning that the 1706 Corbett Stradivari with “W.C.” branded on the bottom rib coincides with Visconti’s return to Cremona, and is the only known Stradivari with a scroll for five strings. Both Corbett and Atillo Ariosti called for a five-metal-string “viol d’amore” for opera arias (distinct from the viola d’amore), and this accords well with “5-hole” violins by Nicolo Amati and Jacob Stainer that featured in Corbett’s will. Whether it was intended to be sent to Corbett in England, or commissioned in anticipation of his arrival in Italy, Visconti seems to have been the likely intermediary, and this unusual violin would seem to be an instrument intentionally made for Corbett’s particular requirements.

Corbett probably left for Italy in 1709 when he received his place in the Royal music establishment. Charles Burney records that he was there in 1710, and that he studied with Corelli, which places his visit before Corelli’s death in 1713. Fifty years earlier, John Bannister, leader of the four-and-twenty fiddlers of Charles II’s court, had taken a similar journey at the outset of his royal patronage to visit Paris and study with J.B. Lully, and it seems that in 1709 Queen Anne was the eager patron of a musician who could bring the latest fashions of Italy back to England. During his frequent returns to the country, a benefit concert for him at Hickford’s Rooms in 1713 included “A Cantato with the Arch Lute, and a new Concerto on the Mandolin, being an Instrument admired in Rome, but never Publick here” as the highlight of a concert showcasing new concertos for a variety of instruments, and the latest developments in Italian opera. Another concert at Hickford’s Rooms in April 1714 was dedicated to showcasing Corbett’s performances of Corelli’s sonatas, perhaps strengthening a case for him having been a recent pupil.

Corbett’s purpose in Italy provided the perfect cover for espionage, and in 1715 a chain of events encouraged the Crown to maintain his position in Italy indefinitely. That year witnessed a Jacobite rising in Scotland and Cornwall, and, simultaneous to its defeat, the death of Louis XIV of France. Up until this point the Jacobite Court in Exile had been in France, but it’s conduct and failures proved a political embarrassment to the French government who were keen to pursue cordial relations with Britain. James Stuart, the Jacobite Pretender, was forced out of France and sought Papal sanctuary in Rome, establishing himself the Palazzo del Re under the patronage of the Pope, with an annuity of 8000 Scudi a year, enough to support his lavish court.

Thereupon Corbett’s mission in Italy seems to have changed, and as an English celebrity his activities were suited to keeping an eye on Jacobite goings on. In 1716, upon the insistence of his wife, he agreed to settle in Milan, but his tour that year of Genoa, Livorno, Rome, Naples, Santa Casa di Loreto and Bologna seems to have been a reconnaissance and information gathering exercise. Over the years that followed, the Jacobite Court acted almost as an unofficial embassy for gentlemen on the Grand Tour, irrespective of politics. Whilst this meant that it could be accessed easily, it also enabled free movement and safe haven of Jacobite plotters. A coded letter from 17 March 1721 from Corbett to his handler back in London provides a series of warnings that indicate gathering forces and the movement of enemies of the state that fit well with the failed “Atterbury Plot”, the attempted coup d’etat intended to take down both monarch and government during the 1722 General Election.

During this period, there seems to have been a brisk trade in old instruments between Italy and England. A report that the cellist Giacobbe Cervetto brought instruments from Cremona to England is confounded by the claim that he had to return them, unable to secure £5 for a violoncello. Corbett would try his luck during his return visit to England in 1723-24 with the announcement of a reserve auction of his collection.

'Corbett's collection is a remarkable reflection of what would be considered the ideal collection today.'

Extract from Daily Journal, 16th May 1724:

“Mr Corbett’s choice collection of musick, to be sold this day, the lowest price being fix’d upon each lot, at his lodgings near the Nag’s Head Inn in Orange Court, by the Mewse: viz, A series of the finest Instruments made by the famous Amatuus’s and old Stradivarius of Cremona, by Gio. P. Maggini, Gasparo da Salo of Brescia; the noted Albani and Stainer of Tyrol, with two fine-toned Cyprus Spinnets, one of Celestini, and the other by Donatus Undeus of Venice. Wherein are the celebrated violins of Gobo, Torelli, N. Cosimi, and Leonardo of Bolognia, which those deceased virtuosos generally played on.”

It seems that his salesmanship was relatively successful, though it is possible that he was trying his luck at high prices rather than trying to liquidate his collection. It is notable that there are no Stradivari violins or Magginis in the collection at the time of his death, nor the “celebrated violins” of Gobo, Torelli, or Leonardo of Bologna. The Hills were the first to point out the phrase old Stradivari, drawing comparison to “Il vecchio Stradivari” by which he appears to have been known in Cremona. It suggests a personal acquaintance with the man, which is all the more likely in view of Corbett’s residency in Milan and his direct connection with Gaspar Visconti and his extensive travels in Italy.

Corbett probably returned to England permanently in 1732, continuing to publish his Universal Bizarris, his collected compositions based on his experiences in Italy, and in 1742 the King granted “Our Trusty and Wellbeloved William Corbett, one of Our Musicians” a fourteen-year copyright on all his printed works. Corbett’s final act was the donation of his collection of instruments to Gresham College, an educational institution in the City of London, which he stipulated in his will in 1747. The collection went further simply than violins, and included Italian paintings, harpsichords, furnishings and collections of his music. ‘I bequeath … my curious Series or Gallery of Cremonys and Stainers violins’. Corbett seems to have made a number of presumptions about the college and what it was willing to accept. One condition was that Bridget Bohannon, one of his executors (and possibly his mistress) would receive lodgings in the college and a stipend of ten pounds per year for life for “her trouble in showing the aforesaid Curiosities at the said College” along with a kindly five pounds to pay her funeral expenses when she died. Ultimately, it transpired that the Professor of Music was renting the proposed gallery space as a warehouse, and was unwilling to lose the extra income. Meanwhile the college authorities decided it would be an unwelcome precedent to provide lodgings for anyone except a professor of the college. Resultingly, they made arrangements for Bohannan’s security, but in 1750 the college authorities disposed of Corbett’s estate. According to Sir John Hawkins, “there was a sale by auction of his instruments at Mercer’s-hall, where many curious violins were knocked down at prices far beneath their value”.

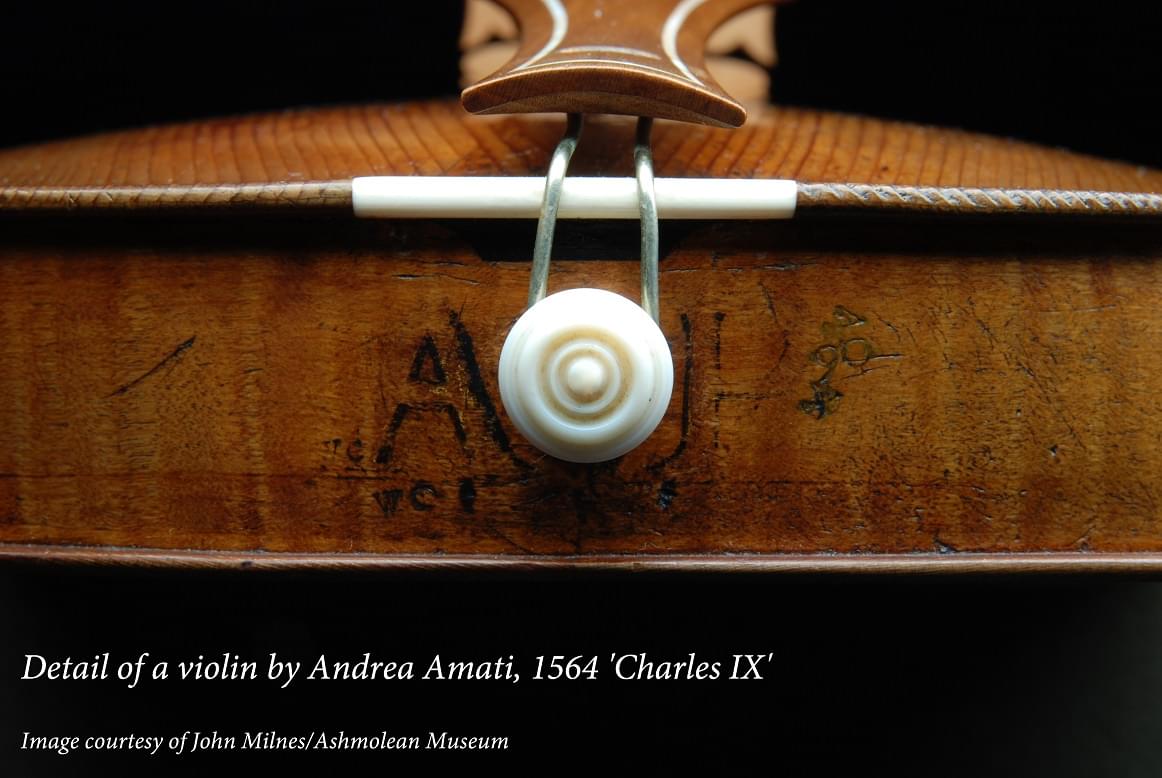

Gresham college had been founded in the Elizabethan period with the purpose of educating merchants of the City of London, and it seems from the description in Corbett’s will that the instruments in the collection were intended as a study collection to be looked at and to remain within the college. This suggests that Corbett’s intentions were to benefit violin makers working in the City of London and to encourage appreciation of Cremonese standards of making. Certainly the collection was extremely well curated to these ends. The will was evidently written by an amanuensis, and there are various confusions within it. In particular, the two Andrea Amadi violins (Corbett uses the spelling found on Andrea Amati’s genuine labels) correspond to the 1564 “Charles IX” violin in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and the 1574 violin in the National Music Museum, South Dakota, if we accept that the dates have been accidentally switched in the will. Both instruments have the same “W.C.” brand on the ribs near the endpin, and a further “44” mark whose purpose is unclear. (It should be noted that the presence of a Charles IX Amati in England as early as 1747 confounds many of the traditional assumptions about these instruments being dispersed at the time of the French revolution. Entries in the Lord Chamberlain’s accounts of the English court show payments for Cremonese instruments being brought over from France in the 1630s by the musician Estienne Nau – perhaps when the plague in Italy made it impossible to purchase violins in Cremona – and that John Bannister submitted receipts for two Cremona violins in 1661 upon his return from studying with Lully in the French court). “A tenor of Grannini of Milan” should obviously be Grancino, whilst there seems to be some doubt about the authenticity of a 1684 Nicolo Amati. Perhaps most curiously of all is the claim of ten bows “by the most eminent masters”, there being little textual evidence that bow makers were held in significant esteem in the 18th century. Altogether, the collection is a remarkable reflection of what would be considered the ideal collection today.

Of all the instruments, only one of them is dated to the period when Corbett was in Italy, a Hieronymus (II) Amati made in 1710. Two things can be said of it from the amanuensis’s description. It had a “whole back”, i.e. a one-piece back, and it was quite a dark violin, because in the slightly conversation-driven inconsistencies of his writing, we know that the 1684 violin that is next on the list was “a paler” one. Thus this satisfactorily describes the Hieronymus (II) Amati bearing identical “W.C.” and “44” stamps to the two Andrea Amati violins also listed in the will. It is incredibly rare to find a Cremonese violin that can be traced back to its first owner. In this case the physical markings of the instrument place it irrefutably within the context of William Corbett’s will. Meanwhile the likelihood that he acquired the instrument in Cremona directly from the hand of the maker seems to fit well within the surrounding evidence and circumstances.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani, Mathias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (5)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (4)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (2)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (9)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (2)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)