A Cremonese Rarity

John Dilworth gives an insight into the work of Giovanni Maria del Bussetto and his Cremonese contemporaries

Giovanni Maria del Bussetto is an enigmatic character in the history of Italian violin making. His work is rare and has in the past been dated to either the 16th or 17th century, depending on whose account you read. Some ascribe him to Brescia, others to Cremona, the city he actually names on his labels.

Furthermore, it is a very familiar name to double-bass players, to whom it represents a particular style of instrument with rounded lower corners, all of which only adds to the confusion. This is in fact a complete misunderstanding based on a single mis-labelled 18th century German double bass. The connection with Brescia might stem from an almost certainly mistaken association of the name with the much earlier Giovanni Maria of Brescia, whose 16th century viols can be seen in the Ashmolean Museum. The enigma of Bussetto has spawned a great deal of speculation, and to a large extent misses his real significance.

The reason Bussetto is so important is that the small handful of labels that do survive give his place of work as Cremona and come from the period 1660 to 1675. The violins (and there are only violins presently recorded, despite the mysterious double bass story) have been given speculative dates as late as 1685, and are in fact very distinctive and consistent, showing great individual character. This was a highly distinguished time and place to be established as a violin maker, so it is astonishing that so little is known about him, given that he worked alongside Amati, Andrea Guarneri, and the young Stradivari.

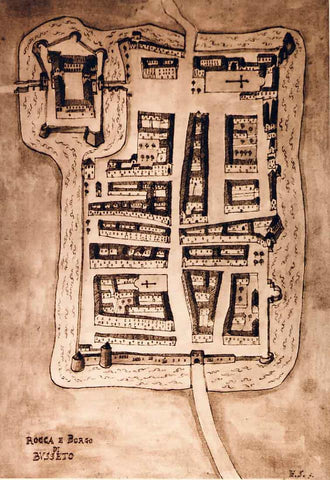

Busseto (in its modern spelling), his presumed place of origin, is a small town near Parma, only 26 kilometres south of Cremona. If he did make the journey to Cremona in search of work, there is no indication that he had any previous experience as a luthier which might have recommended him to any of the workshops there.

In 1660, of course, Cremonese violin making was dominated by the Amati family. Nicolò was in his prime, working with his son Hieronymus II. But he had earlier established a precedent by employing assistants from outside the family, and even from outside the city itself. This is certainly an indication of his Europe-wide success, and the great demand for his instruments. Andrea Guarneri joined him in 1640, G.B. Rogeri from Bologna in 1661, but also, most interestingly, other little known and rarely encountered names like Giacomo Gennaro from Cremona, Bartolomeo Pasta, and one Leopoldo Tedesco, presumably of German origin. These are all recorded as having been part of the Amati household in the middle of the 17th century.

Two great Cremonese names are notably missing from this list, Francesco Rugeri and Antonio Stradivari, but also that of Giovanni Maria del Bussetto.

"Bussetto's violins are in fact very distinctive and consistent, showing great individual character."

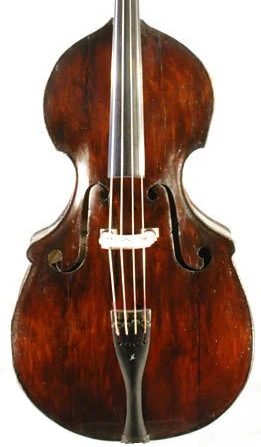

This example, unlabelled but certified by Charles Beare, is a valuable opportunity to examine Bussetto’s work, and understand what he learned in Cremona. In truth, the answer may be surprisingly little.

The most recognisable common factor in Bussetto’s work is the slightly eccentric outline, which can vary somewhat, but usually has rather short centre bouts. This particular violin does not match any of the classical Amati models used by all the other Cremonese makers of the time, and although the form is well governed, it does seem to have an improvised quality.

Looking at it closely, the strongest stylistic link is with the work of the Pasta family, and a good example by Domenico, a son of Bartolomeo, fits this form remarkably well. Most tellingly, the violin shares none of the technical aspects of Amati’s work that Bussetto would have learned if he had been a formal apprentice.

Not only does it lack the geometry, but it lacks the trademark Amati pin at the centre of the back. The interior work is of simple pine rather than willow, and the linings are not morticed to the blocks in the way Amati and all his followers did. What is more, the rib corners are not neatly lapped, but joined in a relatively clumsy way which reveals the joint and the glue line. The f-holes, although neatly formed and cut, are placed very close to the edge.

The scroll, while certainly Amatese, has the slightly heavy quality of a Rogeri. One of the most distinctive examples of Bussetto’s work, the violin once owned by Sir Yehudi Menuhin, has a neatly cut but eccentric scroll with a long, swan-neck throat. The varnish he used however is very Cremonese, and representative of this period, and seems to be the recipe used by both Nicolò and Hieronymus II.

The complexity of the society of violin makers in Cremona in this period is intriguing, and the similarities between this violin and work by the Pasta family is striking. Pasta instruments also lack the technical markers of classical Cremonese work, and it might well be that Pasta and Bussetto worked simply as general assistants, without formal training from the master, not as apprentices who were initiated into the finer aspects of the craft.

Of the other workmen in the Amati shop, Tedesco turned up in Rome sometime after 1654, and Rogeri left for Brescia in 1664. Bartolomeo Pasta established himself in Milan in 1673 at the house of the Testore family, but Gennaro remained in Cremona until his death in 1671. In Milan, Bartholomeo Pasta used labels describing himself as ‘alievo de Amati’, as did his son Gaetano in Brescia, even though in the latter case it could not have been strictly true.

We have no evidence as to how Bussetto spent his career, only the enigmatic but highly significant ‘Cremona’ printed on the known labels of 1660, and two from 1675. He does not make the direct claim to be a pupil of Amati like Pasta does, probably because Amati would not have approved. But it could be said that there are stronger threads binding Bussetto’s work to Pasta’s than to Amati’s, and the story of how the Amati workshop passed its knowledge and experience throughout northern Italy is a rich and intriguing one.

Giovanni Maria Bussetto provides us with a charmingly distinctive legacy of Cremonese violins, although perhaps made on the margins of the burgeoning violin trade of the 17th century.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani I, Matthias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (6)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi Family (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Bussetto, Giovanni Maria del (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (3)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Hill & Sons, W.E. (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Landolfi, Carlo Ferdinando (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (3)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (10)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (4)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)