Norman Rosenberg – The Musician’s Expert

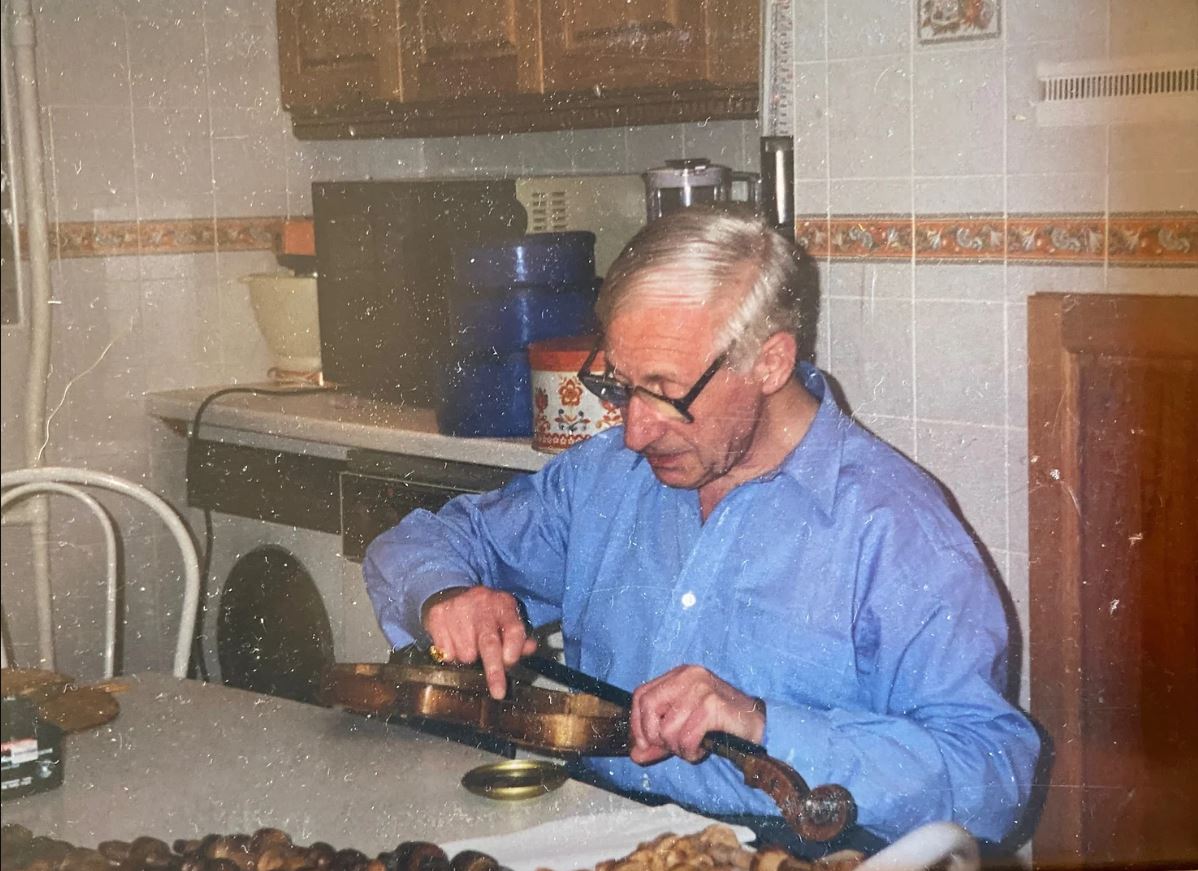

As Ingles & Hayday prepares to sell the private collection of violin expert Norman Rosenberg, Ariane Todes looks back at his life and talks to two violinists who knew him well

Norman Rosenberg, who died in February 2022 at the age of 95, was one of a kind, an old-school gent with a twinkle in his eye. He always stood slightly apart in the violin world – he was only ever interested in the fiddles themselves – but his expertise was acknowledged as among the very best. Not only did he have a superb eye and memory for recognising instruments, but he also had an excellent ear and a code of honour, making him the player’s friend.

Born in Liverpool in 1926, Rosenberg taught himself the violin, inspired by recordings of Heifetz and Kreisler and the concerts to which his grandfather took him. He came from a family of antique dealers, including his father, who had violins in his shop. Combining these skills and passions, he sold his first instrument aged only 20 buying an 1880 Collin-Mézin at a local saleroom for £6, doing it up, and selling it for £8. He was on his way.

'He was completely passionate about violins – he could talk about them forever.'

He once told me in an interview for The Strad, ‘As a provincial schoolboy in the 1930s, my main connections with the violin world were the Liverpool Philharmonic and three violin shops, including Rushworth and Dreaper, where I bought The Strad with sixpence from my pocket money. In those days The Strad had a service called ‘Answers to Correspondents’. I wrote asking about a maker and received a most helpful reply. So, when I came to London some years later, not knowing anyone, one of my first ports of call was The Strad office.’ The story encapsulates Norman – curiosity (bordering on obsession) and a love of good chat. (And a loyalty to The Strad magazine – he placed a small advert in the back pages of The Strad throughout his career.)

Maureen Smith, Professor of Violin at the Royal Academy of Music, got to know Norman when she was a student looking for a violin. She says, ‘He was completely passionate about violins – he could talk about them forever. There was no time limit when you went for a visit. He was in his element talking about violins and telling stories about the great violinists. He’d heard most of them live and knew the sorts of sound they made. He knew everything there was to know about violins and their history.’

'Norman had a photographic memory.'

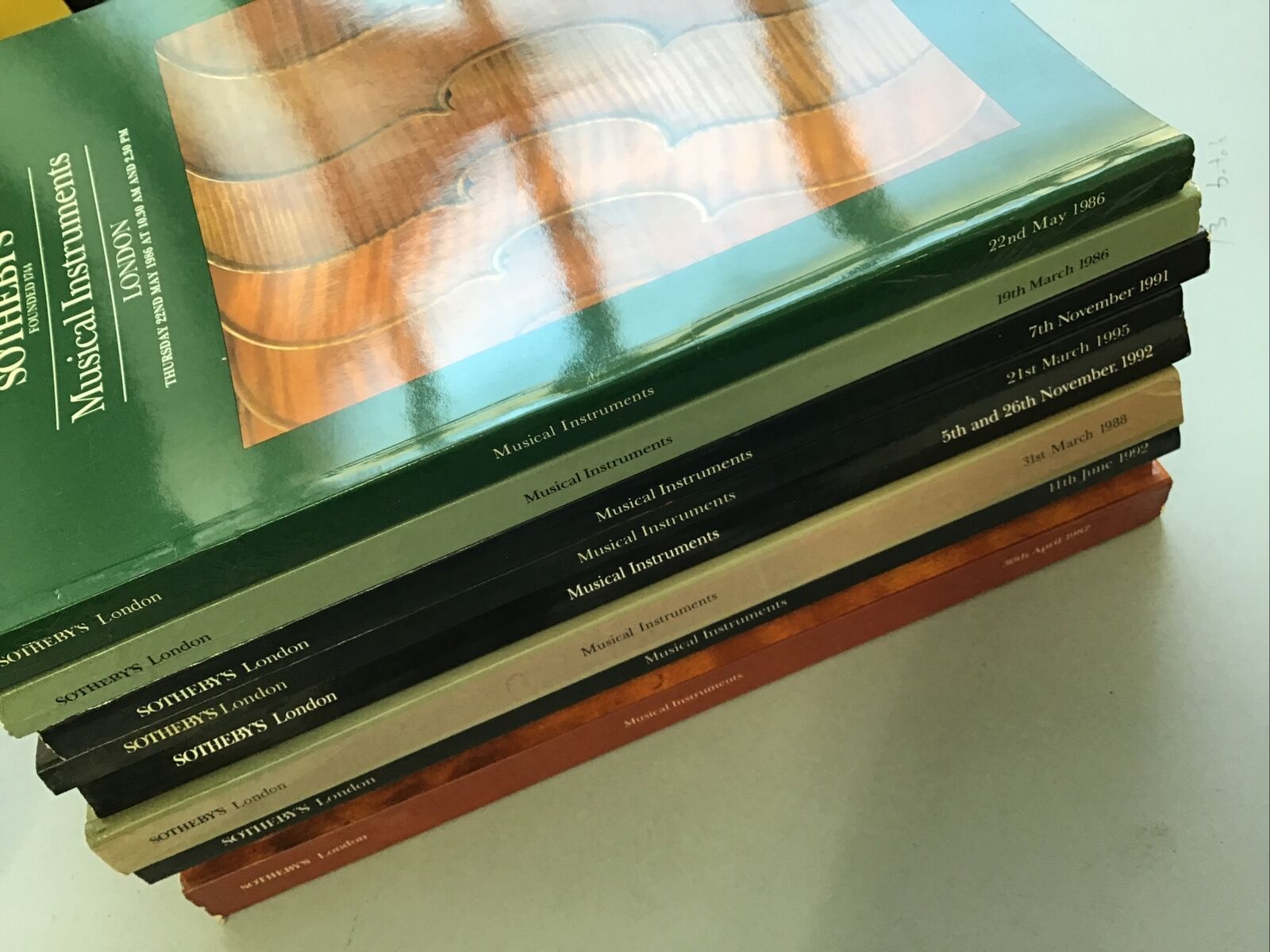

Joshua Fisher, Professor of Violin at the Royal Academy of Music, spent time with Rosenberg from the time he was a student, and remembers his stories, including about the early days. He says: ‘Today there’s a lot of information on the internet, and many books, but back then people had to remember everything – they couldn’t go to their laptop. Norman had a photographic memory. As a young man, he used to hang around Paul Voigt’s shop. It was a tiny one-man operation and Norman was always learning and observing. He said that once someone came in trying to sell a load of scrolls and Norman noticed that one of them was a Testore scroll, which Voigt confirmed. Norman obviously had an eye and an amazing ability. He developed it by looking at real instruments and catalogues and going to auctions.’

Rosenberg’s expertise was such that he could recognise instruments across a room. Smith remembers inviting him to watch a class at the Academy: ‘He came in while I was teaching and walked into this big room. At a distance, he saw the student and he knew immediately not only what instrument was, but also who’d owned it before. He was phenomenal in that way.’

Fisher tells a similar story: ‘He told me that he once went to an auction house and there was an instrument with a bass-bar crack, which had an important certificate. He said, “That’s not a so-and-so. Go to this 1931 catalogue, and you’ll see it’s a twin of that instrument.” They opened the catalogue, found it and agreed.’

This keen sense meant that he had to be careful at auction viewings, though. Fisher explains: ‘He would walk down the instrument tables and stop at each one and have a look, but just for one or two seconds on each side. He said he couldn’t spend longer because if he pored over something, people would see, and he worried they might think it was a good one.’

In a business where deals are often made (and unmade) by alliances, Rosenberg stayed outside the game, by choice, and looked askance at some of the more nefarious practices. Fisher remembers, ‘He told me that years before he had found a sleeper in an auction room and bid up to the level where he bought it. This market price was a lot higher than the other dealers who were bidding together would have gone to. Some time afterwards, he was approached to join that group and he turned them down flatly. He didn’t want to be involved in the “ring”, as he called it.’

Smith says: ‘I really did trust him, in a business where there are very few people you can trust.’ He wasn’t necessarily entirely detached when he looked at instruments that other people were selling, necessarily, though. She says, ‘When I took my current violin to him, he said it was overpriced, which I took with a pinch of salt. He would always be very cautious about giving a valuation, but I knew that unless he damned something, it was a pretty good instrument. He was very hard to please!’

Fisher says, ‘Norman’s opinion was invaluable to me. I would just show him a violin and he would say, “It is what they say, but be careful of this. What are they asking? It’s too much.” And then he’d bring down some of his own violins.’

Trust was a two-way process, and there was a certain process to being allowed to see the best instruments. Fisher remembers the first time he tried Norman’s instruments: ‘He had green baize on his table in his front room and four or five violins lined up, which I tried. I was cheeky – I said I was looking for something better, and he was upset with me. He said, “You can’t try violins so quickly.” I played some more and after ten minutes he went upstairs and came down again with three violins in each hand. He’d managed to wrap his fingers through the pegs – I’ve never seen anyone else do that since. The violins were unbelievable.’

Rosenberg was usually generous in lending his instruments to students and up-and-coming players, but he was notoriously reluctant to actually sell them.

From then on, he would often visit Norman, with Rosenberg’s wife Rosella bringing in tea and biscuits to provide sustenance. ‘Visits would last for some time. He seemed to be very interested in knowing what was going on in the profession and he used to like hearing me play his violins. It wasn’t a simple transaction where I would arrive and within five minutes, I was playing on his good violins, but over one or two hours, he would bring them out.’

Rosenberg was usually generous in lending his instruments to students and up-and-coming players, but he was notoriously reluctant to sell them. Smith explains, ‘They were his family, and he wanted to hang on to them for dear life. He wasn’t really a dealer – he was a collector. He couldn’t see the point of selling. He said, “It’s just more money that I’ll get taxed on.” I wonder if he ever thought of it in monetary terms – that wasn’t really of interest to him.’

As an amateur player himself (he played in the Wembley Philharmonic Orchestra and led the Ben Uri Orchestra, as well as often playing chamber music with friends), Rosenberg had an excellent ear for sound – not always a given with violin dealers and collectors. Smith says, ‘All the violins he collected had a good sound. He never bought something just because it was a good investment. Even with the violins that are going on sale, there’ll be some very valuable ones, but the ones with lesser names will also have a good sound.’

Fisher agrees: ‘He always bought for sound. If he’d acquired something that was a good example of a maker’s work but didn’t work, he would sell it. The quality of sound was always paramount – he was a good fiddle player and knew how to get sound out of a violin.’

This love of sound came from listening to the greats. Fisher says, ‘He had a love for the old school violinists. He remembered the dates of their concerts, the repertoire, how the concerts went. He remembered a particular story about Fritz Kreisler staying with his uncle, and he used to chuckle that Kreisler didn’t practise the whole time of his stay.’

'He gave me a window into the world of violins that I would never have had otherwise.'

This love remained intact even towards the end of his life, when he had Alzheimer’s. Fisher visited him during that time and says, ‘I played recordings to him because I knew he would like that, although I wasn’t sure whether he’d remember the players. I put on a video of Heifetz, and he watched. Within half a second, he said, “That’s the governor.” Then I put on Oistrakh, and he said, “He was probably the best of the lot.” Then Michael Rabin: “He could have been the best of the lot!” You could feel the old Norman there, even when he was ill.’

Fisher explains how his encounters with Rosenberg changed his life: ‘I heard sounds that I’d never heard before. They shook me to the core. As a student, I would never have got to try instruments like that in the big dealerships. He gave me a window into the world of violins that I would never have had otherwise, an opportunity I wish all my students and friends could have – to get into this world of instruments and gorgeous old sounds. I will always be grateful for what Norman gave me.’

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani, Mathias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (6)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi Family (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (3)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Hill & Sons, W.E. (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (3)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (10)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (3)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)