The Golden Age of English Cello Making

In the second of three articles about English cellos, John Dilworth examines a fine Thomas Kennedy made circa 1830

The one hundred years between 1750 and 1850 represent the golden age of English cello making. Perhaps this was inspired by royal patronage, since Frederick Prince of Wales, his successor Prince George (later King George III), and a third Prince of Wales (later Prince Regent and King George IV) were known as cellists. But it was also a period when a series of professional players emerged.

The Italian maestro Giacobbo Cervetto arrived in London in 1728, supposedly with Stradivari cellos he wished to sell. He failed – the conservative English were still loyal to Amati and Stainer – but his son James, born in London in 1748, became an influential player and teacher. James’ pupils included Robert Lindley and James Crosdill, both celebrated and very popular with the new concert-going public in London in the early nineteenth century.

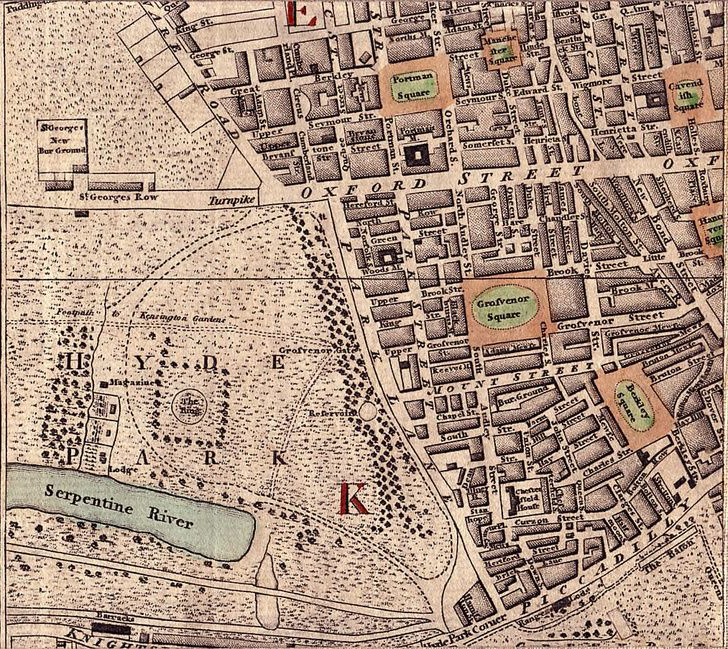

Thomas William Kennedy was born in 1784, and came from a line of violin makers. He was the eldest son of John Kennedy, whose uncle and teacher was Alexander, a pupil of Nathaniel Cross working in Market Street, which coincidentally is now Great Titchfield Street, where Ingles & Hayday is located. Thomas was apprenticed to Thomas Powell, who trained with another great cello-maker, William Forster, with whom Kennedy also worked briefly from 1802. Two years later Kennedy set up his own business at 16 Princes Street, near the Bank of England. Kennedy was clearly ambitious from the outset, and he employed James Brown as an assistant. Brown is credited with a lot of the early output, and this is to an extent borne out by known examples of Browns’ independent work. The influence of Forster is hard to detect, but Simon Andrew Forster, the son of William Forster junior, noted that Kennedy ‘was more indebted to his father [than Forster] for his knowledge of the business, and became a great and good workman…exceedingly quick and rapid in every department’. Kennedy repaid his dues to the Forster family by taking on the young William IV (the son of William junior) as an apprentice, who apparently had a rather wild temperament, and soon left the trade altogether to join a theatrical troupe.

'The cello is made on the familiar Amati model...and is an instrument of the best class of Kennedy's workmanship'

Kennedy’s early cellos, usually signed internally, can be of unexceptional quality with painted purfling, and made on a distinctive Amati model, probably based on an original Amati instrument that had been radically shortened. The typical Kennedy Amati form has disproportionally long centre bouts, with narrowed and shortened upper and lower bouts. It is significant that the Amati form is used over the Stainer model, or imaginary versions of it which were until then the most widely used by cello makers in London, from Wamsley to Forster. From the beginning of his career, the scroll has a consistent feature of having the eye slightly misplaced from the centre, and rather flat undercutting. By 1813 Kennedy had moved west to Nassau Street. An idea of the extent of his business can be gleaned from the records of the Old Bailey, where Kennedy appeared as a witness in 1820, stating that whilst in his parlour, he heard a commotion and was informed he was being robbed. The accused had taken a ‘clarionet’ from behind the counter of his shop. The thief was found guilty and given six months. Kennedy was also at that time selling bows by the leading English makers, Thomas Tubbs and James and Edward Dodd.

Shortly after 1823 the business moved again to 364 Oxford Street, where this particular cello was made, according to the undated label it bears. It was made on the familar Amati model with long ‘C’ bouts, and is an instrument most certainly of the best class of Kennedy’s workmanship, cleanly purfled and well-finished, made with good quality wood. The back is of two pieces of maple cut a little off the quarter with soft flame running horizontally, although it rises a little on the centre right side. The arching is also Amatise in form, with a deep edge-flute rising to a well-rounded centre. The ribs are made from the same wood, while the scroll, as is typical with English cellos in general, is of plain, more easily-carved maple. It is of the classic Kennedy form, with the small eye slightly raised and set back from the centre of the volute, and the undercuts smoothly scraped and slightly concave. The pegbox sides are swept sharply back from the nut, another very English feature that Kennedy dispensed with in the Stradivari models which he began in this period.

In 1849 Kennedy was able to retire, according to Simon Andrew Forster. Although he had married young, he had no children, and the instrument-making Kennedy dynasty ended. Forster estimated that he had made ‘at least 300 cellos, and the other instruments in proportion’.

To view further information on this cello, please click here.

Click here to view other instruments by Thomas Kennedy which we have sold

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani, Mathias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (6)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi Family (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (3)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Hill & Sons, W.E. (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (3)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (10)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (2)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)