The Golden Age of English Cello Making – Part II

In our final article on the subject of English cellos, John Dilworth examines a superbly preserved cello by Bernard Simon Fendt Sr.

Thomas Kennedy and Bernard Simon Fendt represent opposing aspects of the London violin making trade in the early 19th century. Kennedy ran a workshop and music shop which seems to have been almost incredibly prolific, and his signed, dated and labelled cellos (and violins and violas) are well known. Fendt, however, worked primarily for other employers, and his instruments are rarely signed, but often readily identified through the sophistication of his work.

A sea-change occurred in English cello making around the turn of the 19th century with the adoption of the Stradivari model. Giacobbo Cervetto failed to convince English players in 1728, and makers stuck loyally to the Stainer and then Amati forms until the 1800s, when Thomas Dodd and John Betts began to produce copies of instruments which passed through their shops. Dodd certainly handled the 1684 General Kyd Stradivari cello, and Betts was familiar with several, including the 1711 Mara, which came to Betts from the English cellist John Crosdill, and the Schiff of 1698, which was restored in his workshop by his leading craftsman, Bernard Simon Fendt.

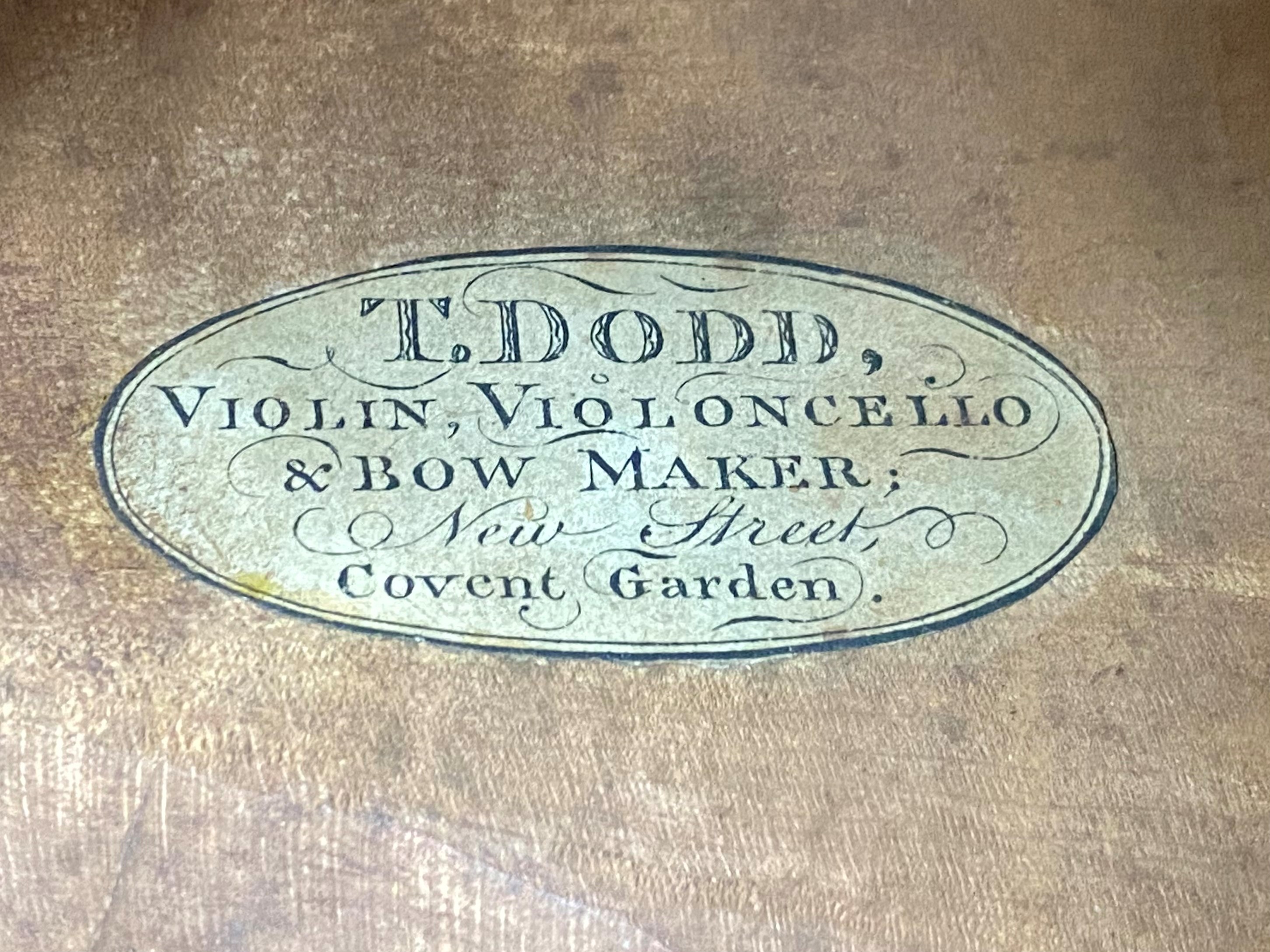

Fendt was born in Füssen and came to work in London in 1798. Between 1809 and 1825 he worked for Betts, where he trained his son, also Bernard Simon (II), who was born in 1801. Father and son both fell into dispute with Betts, the elder Fendt subsequently starting a partnership with Charles Vernon in 1825, until his death in 1832. Before joining Betts, Bernhard Simon Fendt Sr. worked for Thomas Dodd between 1798 and 1809, the period from which this cello, bearing the Dodd label, dates. Unlike Kennedy, Fendt was very rarely able to sign or label his own instruments, and it is possible that his German origins made it difficult for him to set up in business under his own name under the trading laws of the time, as may have been the case with his near-contemporary Vincenzo Panormo. However, the sophistication and craftsmanship of his work and his complete understanding of the Stradivari model makes his work distinctive amongst London makers of the period.

The instrument is an imposing and defining example of Fendt’s work, which possibly marks a high point of London cello-making.

The cello is clearly closely copied from a Stradivari of the ‘B’ form, and covered with the fine varnish that is absolutely characteristic of the maker, in this case in an extremely well-preserved state. It is rich and oily, with a strong red colouration that responds dramatically to differing angles of light, the effect increased by the fine craquelure covering the surface.

The scroll is beautifully balanced and concentric, an accurately observed copy of a Stradivarius, but it is interesting that the chamfers are not stained black, as they would be on an original Stradivari of the period. However, the dark varnish adheres well to the sharp edges, and has a similar effect in emphasising the striking outline of the form. The back has wood of relatively modest but flawless quality, with faint horizontal flame, and the scroll and ribs match well.

The instrument is an imposing and defining example of Fendt’s work, which possibly marks a high point of London cello-making. By the 1850s the exuberant flow of cellos from workshops all over the city seems to have abated, and the energy required to make them in large numbers probably faded with the import of German and French instruments. But the legacy of Kennedy and Fendt, Forster, Dodd, Betts and the numerous other craftsmen working with and for them, is a wide choice of fine instruments of character with a rich and varied history.

To view further information on this cello, please click here.

Read the previous article in the series – a fine cello by Thomas Kennedy

Click here to view other instruments by Bernhard Simon Fendt I which we have sold

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani, Mathias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (6)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi Family (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (3)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Hill & Sons, W.E. (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (3)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (10)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (2)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)