Part IV: Violin Making Outside Cremona

The Evolution of Violin Making from 16th-20th Century

Part IV

The influence of Jacob Stainer

The Amati family and Antonio Stradivari had succeeded in making Cremona synonymous with fine violin making. If you wanted a violin in the 18th century, and you wanted the best, you went to Cremona.

Only Jacob Stainer enjoyed any sort of a comparable reputation at that time. During a fair proportion of the century, Stainer’s designs, although plainly derived from those of Amati, offered an alternative template for makers throughout northern Europe and Italy itself. For a short time, he was the gold standard — even Mozart played on a Stainer violin — and the lighter, more silvery tone of his instruments seemed better suited to the period’s compositional and performance requirements, which were adapting from grand palace ballrooms or outdoor festivals to more intimate chamber recitals.

Stainer’s influence extended briefly to makers in Venice and Florence, but was more marked in England and of course Germany. What is perhaps most remarkable is Stradivari’s foresight in engineering a new violin for the grand stage, for the fireworks of 19th century performance, which ended the fashion for Stainer’s work. There must have been a need for more volume and power in violin tone by 1700, as the other makers in Cremona – Guarneri, Bergonzi and Girolamo Amati II — all quickly followed Stradivari’s lead, but it does not seem to have been fully exploited for another fifty years. Outside Italy, it made little sense for instrument makers to try to compete with the products of Stainer or of Cremona. Because the local clientele would naturally tend to be the less affluent musician, provincial makers offered a cheap alternative. Still, this didn’t prevent them from aspiring to the obvious workmanship and artistry of Amati.

Italian violins came to be viewed as better than any English, French, Dutch or German instrument

The major Italian schools outside Cremona

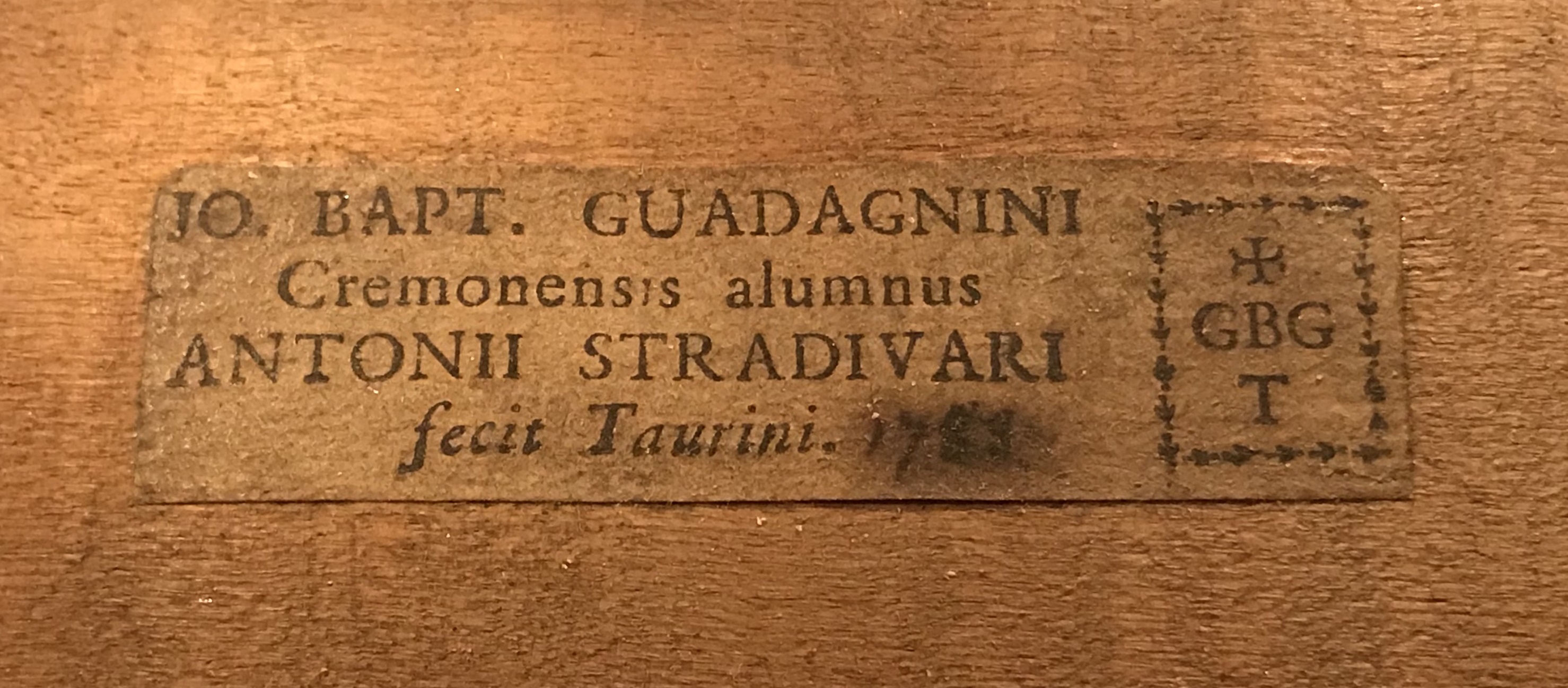

The success of Cremona was to rub off on to all Italian work. Many makers slipped sly references to Cremona onto their labels; spurious pupils of Amati seemed to be everywhere. The address of Montagana’s workshop in Venice was ‘at the Sign of Cremona’. In the same period, Pietro Dalla Costa of nearby Treviso sometimes remarked on his labels that his instruments were ‘exact copies of Amati’. Giovanni Battista Guadagnini of Piacenza, now seen as a great maker in his own right, claimed Cremona as his hometown on labels made after he spent less than a year in the city. By extension, any Italian violin came to be viewed as better than any English, French, Dutch or German instrument, just as French wine is generically assumed to be superior to any other.

But Italy’s reputation for bowed string instruments was built up in an oddly reflexive way. Although Venetians, Bolognese and Brescians were also among the pioneers of violin making, only in Cremona did the craft survive and flourish into the 17th century. When the trade in violins grew in the second half of the century following the plagues, Italy was re-populated by German-trained makers. Virtually all the successful schools of violin making in the 18th century — Naples, Bologna, Venice, Rome and Turin — were sparked into life by immigrant craftsmen, often with direct connections to the small Tyrolean town of Füssen, a traditional centre of skilled woodworking and lute making.

Violin making re-entered Italy via the scenic route, but soon the new professionals became Italianised

Matteo Goffriller, the first of the great Venetian violin makers, came to Venice from Brixen (known to Italian speakers as Bressanone) in the northern Trentino region. In Venice, he joined the shop of the Füssen-trained maker Martin Kaiser. Enricus Catenar brought violin making from Füssen to Turin, and influenced the very stylishly Italian Giofreddo Cappa. Christopher Rittig and Martinus Heel settled in Genoa. Alessandro Gagliano probably learned his craft in Naples from another of the Füssener Kaiser family, and the Augsburg-born David Tecchler established the Roman school.

This repeated an earlier migration: only a few generations previously, the celebrated Füssen-born lute makers Tieffenbrucker and Maler established workshops in Venice and Bologna. Violin making re-entered Italy via the scenic route, but soon the new professionals had fully acclimatised themselves to their new home, and their lutherie became Italianised.

Of the other great traditions, only Milan, Florence and Mantua can be said to be purely Italian, owing their existence respectively, to the Grancino family, Giovanni Battista Gabbrielli, and Pietro Guarneri, the son of Andrea Guarneri of Cremona. Once established, however, the various schools of violin making flourished and developed in a way that outstripped any of their non-Italian rivals.

Why are Italian violins the most prestigious?

It is difficult to say what qualitative differences mark out an instrument made by a Füssener in Italy from instruments made by Füssen-trained makers elsewhere, but there is a consistency amongst Italian instruments that is lacking in others, despite their marked individuality of style. This may be a legacy of the Amatis, but factors such as the placement of the soundholes and the proportions of the body, which make the instrument comfortable and playable for the modern musician, are generally better observed by makers in Italy. Michele Platner and Alessandro Gagliano, both strongly influenced by north-Alpine traditions at first, placed their soundholes very low on the body, creating an awkward string-length and bridge position for present-day players. On the other hand, the Albani family, which worked in the Tyrolean town of Bolzano, made beautiful and elegantly proportioned instruments from the middle of the 17th century onwards. Bolzano, with a mixed population of Italian and German speakers, is the same region from which Matteo Goffriller came. Albani instruments are still commonly described as Italian, and are often mistaken for pure Venetian work.

The instruments of the Gagliano family still command great interest from players as well as collectors

Italian violin making developed and spread quickly. Throughout the 18th century there is little to differentiate the Italian makers from the relatively few other makers abroad, aside from a stylish approach that probably reflects the Italian makers’ extra efforts to earn the premium prices their instruments could command. Even when the conscientious work of the Grancinos in Milan degenerated into the clumsy later efforts of the Testore family, the instruments seem to have retained a certain tonal advantage. The prolific Gagliano family, quick to incorporate Stradivari’s advances into their work in the mid-18th century, also produced many violins of a rapidly and sometimes thoughtlessly worked type. These instruments nevertheless still command great interest from players as well as collectors.

In part five of this series, we discuss Italian tone.

Read Part five here

Read part one: Why Cremona?

Read part two: The Amati Family Dynasty

Read part three: Cremona’s Second Genius

Read part six: The Decline and Renaissance of Italian Violin Making

Click here to view our Notable Sales

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani I, Matthias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (6)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi Family (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Bussetto, Giovanni Maria del (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (3)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Hill & Sons, W.E. (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Landolfi, Carlo Ferdinando (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (3)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (10)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (4)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)