Part VI: The Decline and Renaissance of Italian Violin Making

The Evolution of Violin Making from 16th-20th Century

Part VI

The revival of violin making in Cremona

By the second half of the 18th century, following the deaths of Stradivari and Guarneri del Gesù, Cremona itself was moribund as a centre of violin making. Nevertheless, its renown was still growing and feeding Italy’s reputation for bowed instruments in general. This spurred serious attempts to revive the tradition by makers such as Lorenzo Storioni, whose connection with the great makers was tenuous at best. But a secondary flowering of the Cremonese school did take place in the late 18th century, producing makers like Giovanni Battista Ceruti and Giovanni Rota, whose reputations are growing still. The efforts of collectors and dealers, like the legendary Luigi Tarisio and Count Cozio di Salabue, stimulated public interest in Italian violin making and groomed later makers such as G.B. Guadagnini and the Mantegazzas.

It must have seemed to the outside world that Italy's supply of great violin makers was inexhaustible

When Giovanni Francesco Pressenda and Giuseppe Rocca brought a new energy and impetus to Italian making in Turin in the 19th century, it must have seemed to the outside world that Italy’s supply of great violin makers was inexhaustible. In fact, the effect of the later Turin makers may also have been to show the rest of the world that it was still possible to build good violins.

Around the same time, singularly talented makers emerged elsewhere, and for the first time the pool of great makers appeared to broaden. Joseph Contreras of Madrid benefited hugely from the presence of many Stradivari instruments in that city, and he sparked a brilliant Spanish school of violin making in the late 18th century. Vincenzo Panormo, born in Sicily in 1734, achieved his greatest reputation and effect in London. Nicolas Lupot was born in Stuttgart but worked in Paris, paving the way for J.B. Vuillaume, the best-known and most prolific of all.

How the Italian violin became a historical and collectible commodity

All these craftsmen played a part in defining the 19th century violin, albeit based entirely on the designs of Stradivari and, to only a slightly lesser extent, del Gesù. As part of their craft, these makers, and in particular the entrepreneurial Vuillaume, became dealers, researchers and historians. There was a general realisation by makers that something had been lost in the previous century, whether it was a secret recipe or a particular approach, that needed to be rediscovered. A new breed of copyists and even forgers took over from the artisans of the past who had unselfconsciously produced instruments in their own idiosyncratic style. The pool of old and valuable instruments had increased to such an extent that there was more profit to be made in dealing and imitating old violins than in making new ones. The emphasis of the violin makers business shifted decisively towards old instruments as collectible and valuable items as much as tools of the working musician.

Violins had long been valued both as antiques and mature instruments. Old lutes with a ripe tone were prized more highly than new ones even in the 16th and 17th centuries, and the same notion quickly attached to violins. The sound of stringed instruments unarguably improves with age, but an instrument must be made with a certain delicacy in order to resonate freely. And if made too lightly or carelessly, the instrument will not last long enough to benefit from the effects of time. One of the most important aspects of Andrea Amati’s design for the violin was its strength and durability. Fragile old lutes quickly became irreparable, but violins with their strong, architecturally arched plates and protective overhang around the ribs are not only resilient, but almost endlessly repairable. The rib margin allows the plates to be removed relatively easily, repairs made, and the parts reassembled with considerable tolerance for the shifting tensions and dimensions of such a highly stressed wooden structure. Old violins have survived for far longer than lutes or viols. There are practical limits to the number of times a violin can be rescued from accidental damage, but so far there is no evidence that one can be played-out or exhausted.

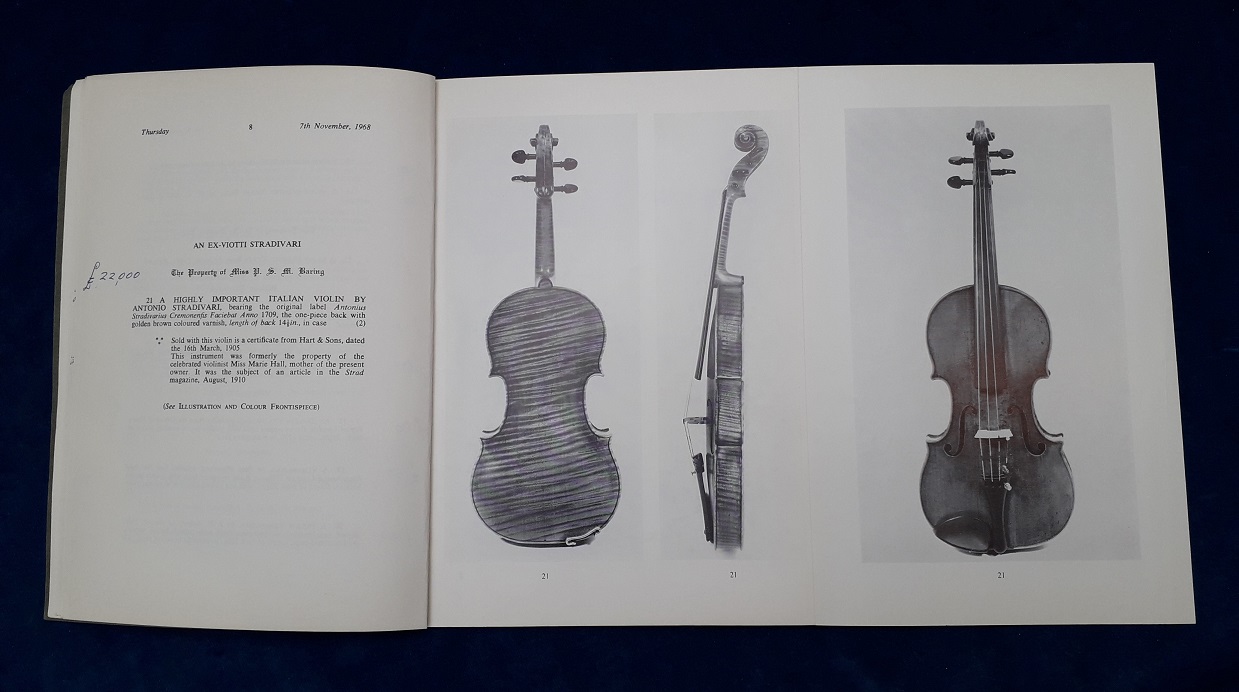

Demand reached new heights when the great Italian players Viotti and Paganini became celebrities

Such enduring quality is obviously a stimulus to investment. As the value of old violins steadily increased, interest shifted from the new products of the workshop to the stock of the dealer’s showroom. Demand reached new heights when the great Italian players Viotti and Paganini became celebrities, in all the modern senses of the word, throughout Europe. Viotti, the ‘father of modern violin technique’, played throughout Europe in the late 18th century and settled in London, where he died in 1829. Paganini came soon after, playing his first concerts to astonished audiences outside Italy in the 1830s. Both men were closely identified with the Stradivari and Guarneri instruments they played, and they stimulated a new market for Cremonese violins. Collecting and acquiring old instruments simply for their status and investment value developed. With this, the unique position of the Italian violin as a supreme instrument of music, a piece of individual craftsmanship of unrivalled beauty, a historical and collectible object, and to top it all, a copper-bottomed investment, was secured.

The names every investor, player and collector knows and looks for are Italian, and the most resonant of them all are Stradivari and Cremona.

To read The Evolution of Violin Making from the 16th to the 20th Century by John Dilworth in full, you can find each part in the links below:

Read part one: Why Cremona?

Read part two: The Amati Family Dynasty

Read part three: Cremona’s Second Genius

Read part four: Violin Making Outside Cremona

Read part five: The Question of ‘Italian Tone’

Click here to view our Notable Sales

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani, Mathias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (6)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi Family (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (3)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Hill & Sons, W.E. (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (3)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (10)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (3)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)