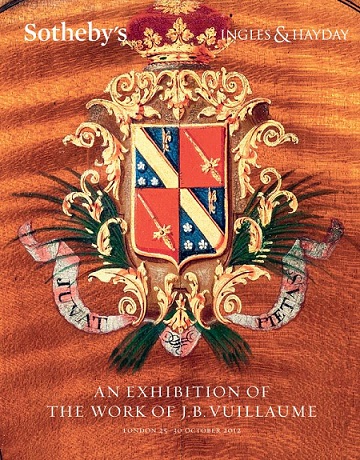

Tim Ingles remembers Sotheby’s Vuillaume exhibition of 2012

Introduction

In the autumn of 2012, which also turned out to be the autumn of my career at Sotheby’s, I had the privilege of handling some of the finest instruments by J.B. Vuillaume, and staging an exhibition of his work in London. This was the culmination of a long love affair with this most exacting of French violin makers, and of my relationship with the collector CM Sin. After the exhibition, CM’s instruments remained with us for sale, and in the early days of Ingles & Hayday we were lucky enough to have ten of the finest Vuillaumes on the planet in our vault. Over the next two years the violins were sold to various professional and amateur musicians and to collectors and enthusiasts, and my deep regret today is that, in the early days of our fledgling business, I didn’t have the presence of mind or the ready cash to buy one of them myself.

At the time of the exhibition we produced a fine catalogue, which is still available, but here we present the exhibition in digital form, along with the text I wrote back in 2012.

June 2020

On a Personal Note

1974 was a big year for me. Mud were at no. 1 in the charts with ‘Tiger Feet’ and I was moving to a new school. My father, rather disappointed that his 7-year old was more interested in Glam Rock than Mozart, took me to the Festival Hall to hear Kyung-Wha Chung play the Beethoven violin concerto. I still have a photograph of my brother and myself, proud in our new school uniform, with our hair touching our collars, on the train to London. 1974 was also the first time I sat at a violin maker’s bench. I remember the light flooding in through the huge bay window at Thomas Smith in Birmingham, as Jan Kudanowski worked on a pretty piece of flamed maple, explaining to me everything he was doing in his inimitable high-pitched voice.

Around the same time, my grandfather was looking for a better violin, and my father found two instruments at the same price for him to choose from. One was early 19th century Neapolitan, the other French and made a few decades later. Knowing a little about violins, my grandfather chose the Italian one. Today his Raffaele Trapani is considered an eccentric violin – an unusual model with idiosyncratic details, and rather difficult to sell. The French violin, the one that got away, was a Vuillaume.

And so the name of J.B. Vuillaume is, in a small way, part of Ingles family lore. Of course it was not until decades later that we realised that my grandfather should have bought the Vuillaume. The popularity of the great Frenchman’s work is a relatively recent phenomenon, as he has thrown off the shackles of being ‘only French’ to become one of the most respected makers and copyists of the 19th century. Only Nicolas Lupot’s and Giuseppe Rocca’s work is undeniably more sought after. Aided perhaps by their ease of identification in a world where authenticity is a constant issue, Vuillaume’s instruments have become a familiar and respected benchmark for musicians and collectors.

In recent years Vuillaume’s reputation as a maker of concert violins has further been enhanced by Hilary Hahn, the first international soloist to regularly use Vuillaume violins (including the ex-Sin 1865 featured in the exhibition) on the concert platform. She has inspired a generation of young violinists, and shown that a 150-year old French violin can, in the right hands, compete with Cremonese violins.

Twenty years later, I retraced my steps and again boarded the London train. This time it was a new life in London and a career at Sotheby’s which beckoned. When I joined, my boss, Graham Wells, had two violins locked away in the cupboard in his office – one was the Pollitzer Guarneri del Gesù, and the other was a Pressenda belonging to CM Sin. This was the first I had heard of CM, a collector of Strads and del Gesùs of apparently mythical status, but it was not long before I had the opportunity to meet him. CM always was, and still is, an intensely private man – principled, meticulous, down to earth and extremely generous. We have known each other for 18 years now, and what began as a business relationship has gradually become a genuine friendship. I am deeply grateful to him for his trust in me, for some of the best Chinese food I have ever eaten, and for the kernel of an idea which has led to this magnificent exhibition.

The Collection

CM Sin has spent much of the last 50 years collecting some of the greatest violins on the planet – Lady Blunt, Dolphin, King Joseph, Booth, Venus, Andrejeus, de Ahna, Lady Inchiquin, Duchess, Archinto, Camposelice – the list reads like a Who’s Who of Strads and Guarneris. But from the early 1970s, CM had also started to collect great copies of Stradivari and Guarneri, made by Giuseppe Rocca and J.B. Vuillaume. The first Vuillaume he bought was the magnificent Saint Nicolas of 1872. One by one, over the following decades, the greatest Vuillaumes available found their way inexorably to CM, and gradually they began to outnumber his Strads and del Gesùs. Today his collection of Vuillaumes is undeniably the finest in the world.

At that time, many people in the violin world must have thought CM Sin was crazy to collect non-Italian violins, but the recent explosion in prices for Vuillaumes has certainly proved him right. When I joined Sotheby’s 18 years ago, a good Vuillaume could be found at auction for around £30,000. Today you would be lucky to buy the same violin for £130,000. An exceptional Vuillaume has always been a match for a good 19th century Italian violin. The unidentified collector who owned the King of Portugal Vuillaume in 1968 bought the violin from Louis Feiler in the mid-1950s, exchanging it for a ‘magnificent’ Pressenda plus $1,200 in cash. More recently, René Morel predicted on page 36 of Violons, Vuillaume that Vuillaume will soon reclaim his place alongside Pressenda. It may not be long now.

CM Sin's collection of Vuillaumes is undeniably the finest in the world.

The highlights of CM’s collection of Vuillaumes are too numerous to list, but include two of the ‘Apostles’, both of which feature in this exhibition, and two instruments from the decorated quartets of 1865 – a violin from the ‘Sheremetev’ quartet and the viola from the ‘Caraman de Chimay’ quartet. Both these instruments have recently been sold, but the viola has kindly been loaned to the exhibition by the new owners, the Chi Mei Foundation of Taiwan. The trio of instruments (two violins and a viola) bought from Vuillaume in 1859 by Dr. William Karrman of Cincinnati are also deserving of a special mention. All three are astonishingly well preserved and, miraculously, all three found their way to CM individually.

Although C.M. Sin’s collection is the centre-piece of this exhibition, his instruments are enhanced and complemented by some extremely fine examples from other owners. The sons of Olivier Jaques, the other great Vuillaume collector of the 20th century, have kindly loaned us four of their father’s finest instruments, including a wonderful viola from 1863 and Isaac Stern’s Tsar Nicholas violin of 1841. The Monaco violinist and collector Danny Spycher has loaned two fine violins from the 1860s, including one of the decorated instruments from the ‘Caraman de Chimay’ quartet. The final touches are two more of the 1865 decorated instruments – the Caraman de Chimay viola and the cello from the ‘Sheremetev’ quartet.

No-one since Stradivari has had such a profound and long-lasting effect on the violin world as J.B. Vuillaume.

J.B. Vuillaume – the man and his legacy

Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume holds a unique place in the history of the violin. As a maker he was the leading light of his generation, but not without peers – Nicolas Lupot and Giuseppe Rocca to name but two. As a connoisseur and collector he was undeniably astute. He secured the majority of Luigi Tarisio’s collection, handled more Stradivaris and Guarneri del Gesùs that any violin dealer before him, and was one of the first to attach his certificate of authenticity to an instrument. As an entrepreneur he was a pioneer, employing the best violin and bow makers of the day, and producing work of such high quality that to use the term ‘workshop’ to describe his output would be entirely inadequate. Vuillaume’s insatiably inventive mind gave us the steel bow, the self-rehairing bow, the octobasse and the miniature self-portrait inside the frog. No-one since Stradivari has had such a profound and long-lasting effect on the violin world. And as he peers down at us imperiously from beneath his fez in the famous portrait in Roger Millant’s book, I feel that if I had the opportunity to meet one violin maker from the past, it would have to be Vuillaume.

The Decorated Quartets

During the course of his approximately 50 years as a violin maker, Vuillaume made a number of special instruments. These were often given names, to distinguish them from the rest of his production, and occasionally they were emblazoned with the coat of arms of the patron for which they were made. The three decorated quartets which were made for Count Doria, Prince Caraman de Chimay and Count Sheremetev are amongst Vuillaume’s most celebrated, and most instantly recognisable instruments.

The ‘Doria’ set dates primarily from 1848, when the two violins and the viola were made, in a mixture of styles (the violins are a Stradivari copy and a Guarneri copy and the viola is made on the Amati model). The cello, however, was not added until 1863, raising the possibility that the commission from Count Doria dates from the early 1860s, and that Vuillaume, having two violins and a viola in stock, made a cello to complete the order.

The two quartets dated 1865 were probably the ones which Vuillaume exhibited in the Paris Great Exhibition of 1867. In September of that year he wrote to François-Joseph Fétis, the Belgian musicologist, ‘I have shown two quartets which embody all that I know, since they are as close to perfection as can be.’ The immodesty is typical of Vuillaume, but the instruments, all made on Stradivari models, bear out his confidence.

The first violin of the ‘Caraman de Chimay’ quartet is undoubtedly one of Vuillaume’s great masterpieces.

The ‘Caraman de Chimay’ quartet was bought from Vuillaume by Victor Charles Antoine de Riquet, second Duc de Caraman. The first violin of this quartet is undoubtedly one of Vuillaume’s great masterpieces – it is illustrated on the frontispiece of Roger Millant’s work on Vuillaume, and was sold at Sotheby’s sale of the Bloomfield collection in November 1988, achieving a world record price of £46,200. The second violin was until recently in the possession of Olivier Jaques of Zurich, and is currently in the collection of Danny Spycher of Monaco. The viola was purchased recently by the Chi Mei Foundation, from the collection of C.M. Sin.

The second quartet dated 1865 was bought by Count Dmitry Nikolaevich Sheremetev, a composer, conductor and patron of the Capella Sheremetev in St. Petersburg. The grand entrance gate of the Sheremetev Palace in St. Petersburg still bears the same coat of arms which can be seen on the back of these instruments. The complete quartet was owned by Alfred Wallenstein in 1962, but after his death his widow sold the quartet via Nash Mondragon of San Francisco, who split it up. The second violin was in CM Sin’s collection from 1986 to 2011, when it was temporarily reunited with the cello at Sotheby’s, before being sold to a European musician. The cello has been with the same American family since 1971, and we are grateful to them for making it available for this exhibition. The Sheremetev cello was sold by Sotheby’s in 2012.

The Apostles

Between 1863 and 1875 Vuillaume made a number of instruments dedicated to saints. The catalogue of the 1998 Vuillaume exhibition in Paris notes that Vuillaume produced around a dozen instruments bearing the names of saints, of which nine are known to us.

The first four of these instruments date from 1863, when Vuillaume made the quartet known as The Evangelists. Whereas the two decorated quartets of 1865 are both numbered in ‘reverse’ order, with the cello first and the first violin last, the Evangelists are numbered as one would expect, with the first violin numbered 2501 and the cello 2504. They are named St. Jean, St. Marc, St. Mathieu and St. Luc, which is plainly in contrast to the traditional ordering of the gospels, and to the order in which they were written (generally considered to be Mark, Matthew, Luke, John). Quite why Vuillaume ordered the Evangelists in this way remains a mystery, but it is not surprising that he chose to name the first violin after St. John, who was, and indeed still is, considered by many to be the most important of the Evangelists.

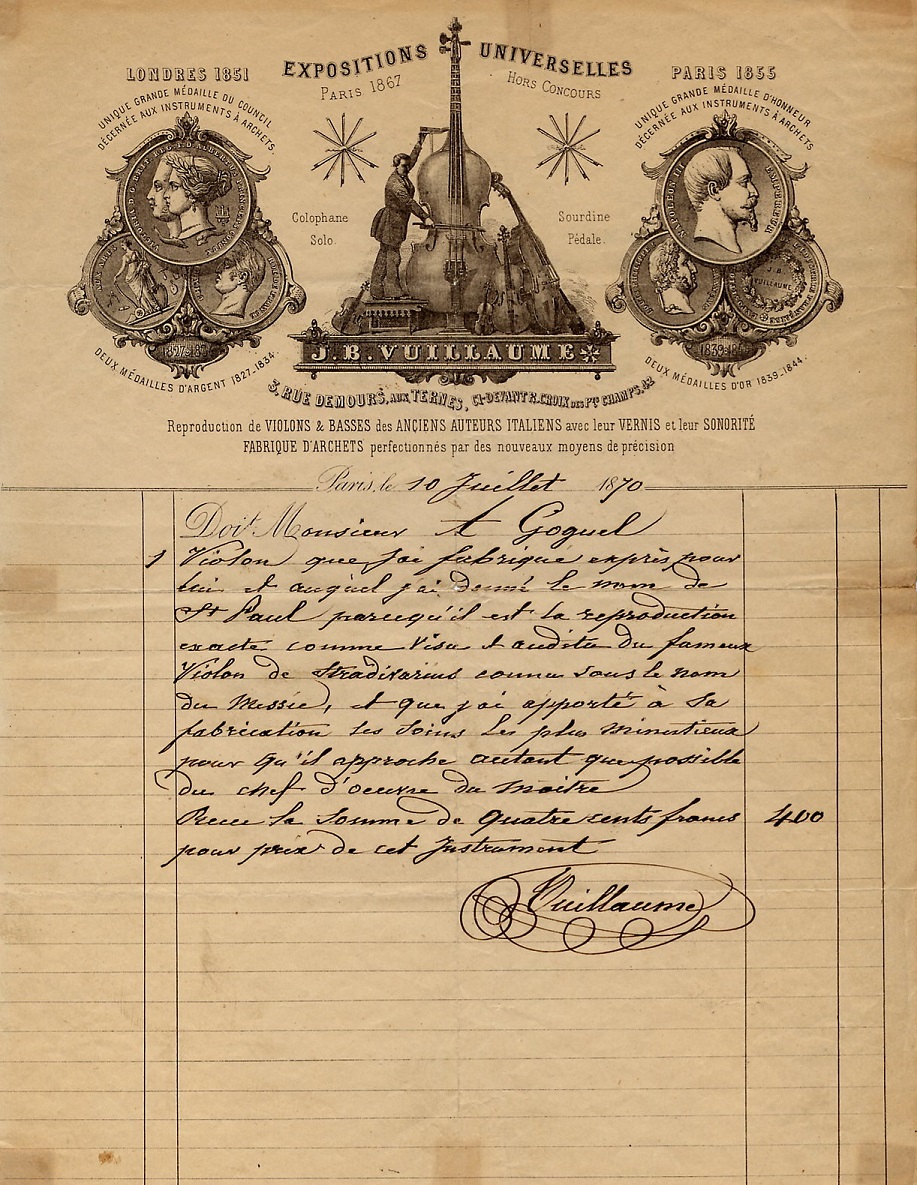

In the same year, Vuillaume made the St. Joseph violin, and in 1864 St. Peter and St. Paul followed, both of which bear the name of the saint inscribed below the bridge, as do the Evangelists. St. Peter is today held in the Russian State Collection in Moscow, and St. Paul is in private hands in the US. In 1870 Vuillaume made another violin which he christened St. Paul, presumably at the request of his client, a Monsieur Goguel. He carved a tailpiece with the image of the saint, and wrote a letter explaining that he had named the violin St. Paul as it was an exact copy of the Messie Stradivari. Probably the last of the named instruments is the St. Nicolas, a Stradivari copy made with a stunning single piece of strongly flamed maple, which dates from 1872.

The Evangelists quartet was sold at Ingles & Hayday in 2016. Please click here for more information.

Decorated violin after Stradivari, 1841,

ex-Stern, the Tsar Nicholas

This violin, the only example of Vuillaume’s work from the 1840s in the exhibition, appears to be based on Stradivari’s model of around 1707-8. The stunning one-piece back calls to mind some of Stradivari’s great violins of 1709 and 1710, notably the Viotti; Marie Hall. The violin has been antiqued, partly by Vuillaume himself, and partly by use, and bears the label Fait à Paris par J.B. Vuillaume pour A. Lvoff l’an 1840. Although the label bears the date of 1840, the pencil date in the upper back reads 41, suggesting that the commission was not completed until the following year.

Alexis Feodorovich Lvoff was a talented Russian violinist, conductor and composer. Born in 1799, he joined the Russian army as a young man and enjoyed rapid promotion, becoming adjutant to Tsar Nicholas I. In 1833 he was commissioned by the Tsar to compose the Russian national anthem, probably most famous for its appearance in Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

In 1840 Lvoff made a concert tour to Leipzig and Paris. There he visited Vuillaume, commissioned the violin and presumably requested that Vuillaume decorate the back of the instrument. The coat of arms on the back is the subject of some controversy. It appears not to be that of Tsar Nicholas I, but is in some way connected to his predecessor Tsar Alexander I, who reigned from 1801 to 1825. The motto on the coat of arms, which means ‘God save the Tsar’, was a favourite of Alexander I, and the white rose on the left signifies the birthday of his sister-in-law, Alexandra Feodorovna.

Sadly all paperwork relating to the violin has been lost, so its subsequent history is unclear, but it was in the possession of Isaac Stern before joining the collection of Olivier Jaques of Zurich. It bears Vuillaume’s serial number 1431.

Violin after the Cannon Guarneri, 1854

In 1836 Paganini brought his Guarneri violin to Vuillaume in Paris for repair, and Vuillaume is said to have been captivated by it. Until that time Vuillaume’s work was based on various different models, with Amati and Maggini featuring heavily, but from 1840 his work is dominated by Stradivari and Guarneri copies. Almost all of his Guarneri model violins are copies of, or interpretations of, the Cannon.

The blackening of the front of this violin, and its wild, open scroll both mimic Paganini’s violin. Yet Vuillaume chose a strikingly flamed single piece of maple, often seen in his Guarneri copies of this period, and quite unlike the rather understated two-piece back of the original.

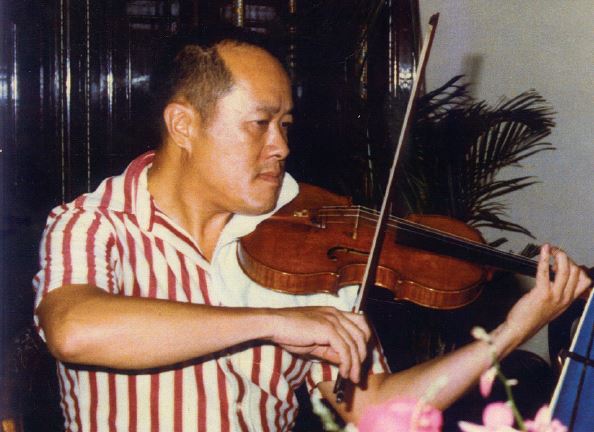

In 1987 this violin was sold to Hu Kun, widely celebrated as the first mainland Chinese violinist to establish a solo career on the international platform. He was a protégé of Lord Menuhin, who advised him to acquire this instrument with the proceeds of his competition successes. It has been his concert violin since that time. In 1997, Hu Kun gave the first performance of the Elgar Violin Concerto in China on this violin, with Menuhin conducting.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, rue Croix des Petits Champs, JBV, the violin is numbered 1966.

Violin after the Cannon Guarneri, 1854

This violin offers a fascinating contrast to the previous instrument. Both made in 1854, both inspired by the Cannon Guarneri, this later violin (44 later in Vuillaume’s numbering sequence) is so well preserved that we can devine the maker’s original intentions, undiluted by age or use.

The tell-tale darkening of the central area between the f-holes, and the particularly upright setting of the treble f, mark the violin out as a copy of the Cannon. The wood of the back displays Vuillaume’s tendency to place the figure horizontally or slightly ascending from the joint on his Guarneri models, as is the case with the Cannon itself. The purfling is deliberately inlaid innacurately, but interestingly the scroll conforms to the generic ‘del Gesù’ pattern which Vuillaume used, based on del Gesù’s work circa 1741-2, rather than the wilder scroll seen on the other 1854 Cannon copy.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, rue Croix des Petits Champs, JBV, this violin is numbered 2110.

Violin after the Messie Stradivari, 1856

The tale of how Vuillaume acquired the Messie Stradivari from Luigi Tarisio in 1854 is probably the best known story in the violin world. It is not difficult to imagine Vuillaume opening the double case containing Le Messie and the Alard Guarneri on his return to Paris, marvelling at their freshness, and being impatient to make copies. Given the plethora of Messiah copies which left Vuillaume’s hand over the next twenty years, it is surprising that there are so few, if any, of the Alard del Gesù.

This violin is one of the earliest copies of Le Messie and also one of the most accurate. Vuillaume obviously went to great lengths to match the wood of the front and back, and his attention to detail even extended to matching Stradivari’s slightly overshot purfling mitre on the lower bass corner on the front. Like its inspiration, this violin is astonishingly well preserved, and is one of the jewels of the collection of Olivier Jaques.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, rue Croix des Petits Champs, JBV, it bears Vuillaume’s serial number 2173.

Viola after Stradivari, 1859

ex-Karrman

This viola was featured in the September-October 1960 issue of Violins and Violinists, which states that on 27th July 1859 J.B. Vuillaume issued a receipt for two violins and a viola to his friend Dr. William Karrman of Cincinnati. Given the extraordinary state of preservation of all three instruments, it is hard to believe the following sentence: ‘the instruments were used by Dr. Karrman during his lifetime and were, on occasion, lent to professional violinists for concerts in Cincinnati.’

Both the magazine and the subsequent Lewis certificate describe the viola as a handsome example, one of the finest known to them, and the instrument certainly lives up to its reputation. It is, like the other two violas in the exhibition, unusual in that it is one of only a few which Vuillaume made on a larger model, with a back length of about 414mm (16¼ inches), in contrast to his usual 395mm (15½ inches). The model is clearly inspired by Stradivari, and the bold red of the varnish is reminiscent of the height of Stradivari’s career. Unlike the 1863 viola below, this instrument seems to be an interpretation of Stradivari, rather than a copy of a particular viola.

After Karrman’s death in the late 1950s, the trio was acquired by William Lewis and Son, and the viola was sold to a Mr. Gene Adams of Illinois in 1962. It was purchased by C.M. Sin in 2010.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, it is numbered 2315.

Violin after Stradivari, 1859

ex-Karrman

It is difficult to imagine a more magnificent Stradivari copy than this. Its broad edges, unusually wide purfling and full arching speak of the middle of Stradivari’s Golden Period. The setting of the f-holes and the wear pattern of the varnish on the back suggest that the Alard of 1715, which was probably in Vuillaume’s possession at the time, may have been the inspiration for this instrument. With just a little deliberate ageing below the feet of the bridge and in the four corners of the front, it gives us an idea of what most Strads must have looked like in Vuillaume’s day. The deliberate wear on the upper back edge of the pegbox, which, unusually for Vuillaume, is rather crudely executed, enhances the impression that Vuillaume

was copying a specific instrument.

This violin was acquired by Wiliam Lewis & Son from Dr. William Karrman. Lewis split up the trio, selling this instrument to a Mr. Rudolph Onofreyo of Montreal. In 2004 it was in the possession of Mr. John Hughes of Washington, D.C., and shortly afterwards became part of the collection of C.M. Sin.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, it bears the serial number 2316.

Violin after Guarneri, 1859

ex-Karrman

The back of this instrument, the final instrument made for William Karrman, is not dissimilar to the 1854 Guarneri model violin above. The wood choice and wear pattern of the back are strikingly similar, yet the front is given a quite different treatment. The model is clearly that of the Cannon, but rather than blackening the front in the style of the original, Vuillaume uses minimal antiquing, with only tiny traces of distressing by the bridge feet. This feeling of preservation is enhanced by the extraordinary state of this violin, with the original patina of the varnish still clearly visible on the front and back.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, it is inscribed internally with the serial number 2317. The bridge, stamped H.C. Silvestre, must have been on the violin for at least 100 years. Before being acquired by C.M. Sin in September 2000, the instrument had been in the same family for four generations.

Violin after the Cannon Guarneri, 1861

Most of the features of Vuillaume’s Cannon copies are stylised – the f-holes cut rather too cleanly, the purfling inlaid untidily, but still rather more accurately than del Gesù himself would have done, and the excesses of the scroll watered down. In other words, rarely do we see what we would today call a ‘bench copy’ from Vuillaume’s hand, and any stories about Paganini mistaking Vuillaume’s copy for the original are probably apocryphal. Vuillaume undeniably captures the flavour of the Cannon, and his copies are probably more recognisable than the Guarneri itself, but it is fair to say that Vuillaume, who was one of the finest copyists ever, intended his Cannon copies to be interpretations rather than exact copies.

This fine example is typical of that impressive but slightly stylised approach, and formed part of the collection of Olivier Jaques, alongside a similar example from 1869. Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, it is numbered 2402.

Violin after the Cannon Guarneri, 1862

ex-Sin

By the early 1860s Vuillaume had been copying the Cannon for 25 years, and gradually his preference for copying Le Messie became apparent. The Guarneri copies become rarer as we move through the 1860s, and this is the penultimate Guarneri model instrument in the exhibition.

C.M. Sin purchased this violin in 1975, at which time Charles Beare wrote to him saying ‘this is one of the great ones and I am glad you have it.’ The striking flame of the back, ribs and scroll, and the contrast between the deep red-orange of the varnish and the golden ground of the antiqued central area of the back certainly make this a visually arresting instrument. C.M. Sin owned the violin for 33 years and finally parted with it in 2008, to Danny Spycher, a Swiss violinist and collector. Spycher was a pupil of Nathan Milstein and grew up in a musical family where Clara Haskil and Artur Grumiaux would visit to play chamber music.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, the violin is numbered internally 2410.

Violin after the Messie Stradivari, 1863

ex-Sin

This violin is the first of three almost identical Messiah copies in the exhibition, dated 1863, 1871 and 1873. It is labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes in the usual way, but Vuillaume chooses to preface this with an additional label with the words Imitation précise du Stradiuarius du Comte Cozio de Salabue, daté 1716. Le “Messie” fait par.

Vuillaume’s claim to have made a precise copy seems entirely valid – the flame of the back, gently descending from the centre joint, and the slant of the f-holes leave us in no doubt as to the inspiration for this violin, though the grain of the front is possibly a less faithful match than that of the 1856 violin above. There is a slight red-brown tinge to the varnish, making it a shade or two deeper than the usual golden orange of the Messie copies.

The violin was certified by W.E. Hill & Sons in 1954 as being in the possession of a Mr. W. Sutherland of Edinburgh, and was sold by Balmforths in 1955 to an American gentleman by the rather Scottish sounding name of Mr. Clyde Banks. Inevitably, it subsequently found its way into the collection of C.M. Sin. The violin bears Vuillaume’s serial number 2488.

Viola after Stradivari, 1863

ex-Sin

This instrument presents a marked contrast to the 1854 viola, which is modelled on a longer form of the standard Stradivari-inspired model which Vuillaume used for his 15½ inch violas. This 1863 viola is one of only a few which Vuillaume made with a back length of 16¼ inches, of which three are exhibited here. It appears to be based on a particular Stradivari viola, possibly the Russian of 1715, which forms part of the Russian State Collection in Moscow.

This instrument is not antiqued at all, yet the subdued golden-brown of the varnish gives an impression of age, something which certainly cannot be said of the pristine look of the antiqued 1854 viola. On closer inspection, however, this viola is very well preserved, and in many ways is a viola-sized older sibling to the Messiah copy violins which Vuillaume produced in the 1860s and 1870s.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, it bears Vuillaume’s serial number 2494.

Violin after Stradivari, 1865

ex-Sin

At first glance, this instrument bears a strong resemblance to the 1859 Stradivari copy above. They are certainly made on the same model, with the same full arching and the treble f-hole set a little high in the Stradivarian style, and at a slightly steeper angle. But the detail reveals a difference in approach, particularly in the varnish.

It is rare to see a Vuillaume which has varnish of this soft, warm texture. It is translucent in a subtle way, as close to a Cremonese varnish as one sees outside Cremona, and the soft texture reduces the contrast between the varnish and the bare wood on the back, which can often be very stark in Vuillaume’s work. The fact that the violin has not been polished gives the varnish a dry look not unlike the Betts Stradivari, and the original patina is visible between the bridge and tailpiece, and in various places on the back. The magnificent 1870 Cannon copy on page 39 shares this varnish, although it is a little more polished.

This violin is labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, and bears Vuillaume’s serial number 2591. It was acquired by C.M. Sin in 2001 and was sold to Hilary Hahn in 2013.

Decorated cello after Stradivari, 1865,

ex-Sheremetev

The only cello in the exhibiton was made on an unusually large pattern, apparently inspired by Stradivari’s pre-1707 model. The body is 30 1/16 inches in length, and the lower bouts almost 18 inches wide (456mm.). This magnificent sounding cello is truly a solo instrument. It is very well preserved, although the wear on the treble shoulder of the back indicates that it has had regular use over the last 150 years.

The cello is part of a quartet bought from Vuillaume by Count Dmitry Nikolaevich Sheremetev, who was a composer, conductor and patron of the Capella Sheremetev. The Sheremetev Palace in St. Petersburg, which is now a museum, still bears the family’s coat of arms, which was emblazoned on the back of all four instruments.

The cello has been in the US for almost 100 years. In 1929, Wurlitzers sold it to Francis C. Dale, and in the early 1960s the whole quartet was in the possession of Alfred Wallenstein. The quartet was acquired from Wallenstein’s widow by Nash Mondragon, who broke it up, and it appears that the first violin and the cello were both sold to Norman and Madeleine Goss. Norman Goss retained possession until 1971, when he sold the cello to the family of the current owner for $10,000.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3 rue Demours Ternes, à Paris, JBV, the label is inscribed with the date 1865, and the cello is numbered 2602.

Decorated viola after Stradivari, 1865,

ex-Caraman de Chimay

The quartet of instruments bought from Vuillaume by Victor Charles Antoine de Riquet, second Duc de Caraman, is probably the best known of Vuillaume’s decorated quartets. Legend has it that the quartet was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1867 in Paris, where it was spotted by the duke, who presumably requested that his family’s coat of arms be added to the instruments. The quartet had been completed in 1865 and the instruments are numbered 2609-2612, with the cello numbered first.

It is likely that the complete quartet was purchased directly from the Caraman family by W.E. Hill & Sons, who sold the viola and the violin numbered 2611 to Nathan Posner in 1923. It is very exciting to be able to present these two instruments side by side, reunited 89 years later.

In 1954 the viola was sold by Wurlitzers to Carl J. Eberl of Reading, Pennsylvania. In 1993 it was in the possession of Yoshihiro Sawada, and it was acquired by C.M. Sin in 2005. In 2011 it became part of the collection of the Chi Mei Foundation of Tainan, Taiwan.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, it bears the serial number 2610.

Decorated violin after Stradivari, 1865

ex-Caraman de Chimay

Given Vuillaume’s obsession with Le Messie, the 1716 Stradivari which was his pride and joy, it is not surprising that his two quartets dating from 1865 are matched sets, with all four instruments made on the Stradivari model.

The first violin, sold at Sotheby’s sale of the Bloomfield Collection in 1988, and illustrated on the frontispiece of Roger Millant’s book J.B. Vuillaume, was made with a single piece of strikingly flamed maple, whereas the second violin is somewhat understated, aside from the spectacular coat of arms emblazoned on the back.

This violin was sold by W.E. Hill & Sons to Nathan Posner in 1923, together with the ‘Caraman de Chimay’ viola, and subsequently passed to Sol Kinder and Louis Feiler, who owned it from 1938 to 1948. Whilst in Feiler’s possession, both instruments were featured in Ernest Doring’s pamphlet Violins and Violinists. The violin was sold to Olivier Jaques around 1980, and remained with the Jaques family for thirty years, before being acquired by Danny Spycher at Sotheby’s in 2009.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, and inscribed 1865 on the label, the violin is numbered internally 2611.

A violin after the Messie Stradivari, 1870

Saint Paul

The history of Vuillaume’s series of instruments known as ‘The Apostles’ is explored fully on page 5. This violin was undoubtedly a specific commission from a Monsieur A. Goguel, to whom Vuillaume made out the original receipt on 10th July 1870 (see above).

Vuillaume states that he has given the violin the name Saint Paul because it is an exact reproduction ‘in visu et audito’ (in sight and sound) of the Messie Stradivari. Again we encounter Vuillaume’s rather loose interpretion of the phrase ‘exact reproduction’, as he chose a single piece of broadly flamed maple for the back, but the prominent grain of the front and the delicately carved tailpiece and pegs add to the feeling of authenticity.

This violin has attracted superlatives ever since it was made. In 1949 it was in the possession of Edgardo Acosta of Paris, at which time it was described by Silvestre & Maucotel as ‘d’une conservation parfaite’ and ‘un des plus beaux spécimens que nous ayons connu’. In the same year H. & C. Tournier added their own comments: ‘exemplaire rare, de toute beauté, et absolument intact’. It was subsequently owned by W. Dean Lucien of Sherman Oaks, California, and in 1961 it belonged to John Malchan of Montclair, California. On 23rd November

1988, the same day that the first violin from the Caraman de Chimay quartet was sold at Sotheby’s, the St. Paul was auctioned at Christies for £41,800. The buyer was C.M. Sin.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, with the date inscribed faintly on the label, it is numbered 2809.

Violin after the Cannon Guarneri, 1870

ex-Robertson

This is a magnificent violin in every way, and fully deserves the secondary label which Vuillaume inserted in a select few instruments, describing it as Imitation exacte du “Joseph Guarnerius” de “Paganini”. As is the norm with Vuillaume, he did not restrict himself to slavishly copying the Cannon, but successfully captured the overall impression of breadth and power and the visual impact which the original conveys.

Interestingly, despite its claim to be an exact imitation, there is no attempt to inlay the purfling in an untidy manner, as with all four previous Guarneri model violins. In fact this violin has slightly longer corners than usual, and the purfling sweeps elegantly into the corners with tiny bee-stings, giving it a slightly more finessed appearance. This is matched by a rich golden-orange varnish of breathtaking quality. The customary deliberate antiquing is also in evidence, using subtle brush strokes on the front, and even on the back of the pegbox. The final masterstroke is a piece of spruce for the front which has a line of darker close-grained wood running through the treble f-hole, a feature often seen in del Gesù’s work.

This instrument, labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, bears the inscription on the label exprès pour Mr. James Robertson and is numbered 2821. It was sold by Wurlitzers to Mr. Nicholas Pisani of North Hollywood in 1943, and acquired by C.M. Sin in 2005.

Violin after the Messie Stradivari, 1871

ex-Posner

On page 19 of their monograph on Le Messie, entitled The Salabue Stradivari, W.E. Hill & Sons write about Vuillaume’s reproductions of Stradivari: ‘These instruments, imitations though they were, had high intrinsic merit; and it is to be remembered that they were copies made from unrivalled models, with a fidelity and care such as only a devoted worshipper and a great master of this art could attain. He spared no pain in striving after perfection in the quality of his materials, and he treated the obscure and difficult problem of varnish (the secret

of which, as applied by the old Italian masters, seems to have died with them) with a success which has probably not been equalled by any other maker since their time.’

But for the slightly lighter varnish, this violin is practically indistinguishable from the 1863 Messiah copy above. It is listed on page 127 of Roger Millant’s book as one of the ten most noteworthy of Vuillaume’s Messiah copies.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV and inscribed 1871 on the label, the violin is numbered internally 2853. It was previously owned by Nathan Posner, and was acquired by C.M. Sin in 2009.

Violin after the Messie Stradivari, 1871

ex-Sin

The final two Messiah copies in the exhibition are a testament to the extraordinary consistency of Vuillaume’s work. This violin and the King of Portugal below are practically twins, but for the difference in wood choice for the back. The quality of materials and workmanship are beyond reproach, and matched only by the astonishing state of preservation of both violins.

This example, with its stunning one-piece back, was christened The New by C.M. Sin, who has owned it for 12 years. The crispness of the scroll, with the blackened chamfer entirely intact, is breathtaking, and the only sign of Vuillaume’s advancing years (he was 73 when the violin was made) is the slightly misplaced and unusually large upper locating pin, which has been sliced through by the perfectly inlaid purfling.

The violin is labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV. Unusually for a violin of this date, there is no date inscribed on the label, but Vuillaume’s serial number 2874 is crystal clear on the central back.

Violin after Stradivari, 1872

the Saint Nicolas

Although Vuilllaume’s latter years are dominated by copies of Le Messie, there are occasional bursts of creative imagination, and without doubt this violin represents one of the pinnacles of Vuillaume’s career as a maker.

On seeing this violin, it is difficult not to speculate immediately as to which Stradivari Vuillaume was copying, and the Viotti of 1709 in the collection of the Royal Academy of Music seems a possible candidate. A back of such eye-watering flame calls to mind a particular log which Stradivari used in 1703-4 and can be seen on the Emiliani and Sammons violins of those years. But the broad, flat model speaks of the years 1709-1717, and the golden-orange varnish, rich and translucent, is of Vuillaume’s best type.

Vuillaume made the instrument for the collector Nicolas de Haller of St. Petersburg, and his typically immodest letter of 11th September 1872 to de Haller describes the violin as ‘l’instrument que j’avais soigné tout particulièrement pour vous, comme aux quelques instruments extraordinaries que j’ai fait, je leur ai donné des noms pour les dinstinguer, celui ci à votre intention s’appelle St. Nicolas… je ne crois pas en avoir fait un plus complet, ni mieux réussi, le bois, le travail, le vernis sont splendides.’

By 1948 the violin was in the possession of Monsieur Lazare Rudié of New York, and at the time Emile Français described it as a ‘magnifique exemplaire fait en copie de Stradivarius’. When William Moennig & Son sold the violin to C.M. Sin on 31st January 1972, they noted ‘a magnificent example… in a perfect state of preservation’.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, the violin is inscribed on the label Dédié à M. Nicolas de Haller, 1872. Unusually, the signature in the upper back also includes the words Exprès pour M. Nicolas de Haller, 1872. The instrument has previously been thought to be numbered 2908, but the last digit of the pencil number in the central back has been altered to 8, whereas the number inscribed by the top block is clearly visible as 2903.

Violin after Stradivari, 1873

the King of Portugal

It seems fitting to end our exhibition with this beautiful copy of Le Messie, a violin which was not only Vuillaume’s most treasured possession, but also the single greatest influence on him as a maker. There remains little more to be said about the quality of Vuillaume’s best Messiah copies, and Vuillaume was in no doubt that this one ranked amongst his best work, giving the violin his secondary Imitation précise… label.

The history of this instrument adds to its charm, as it was made on the instructions of King Pedro V of Portugal. The king had seen Le Messie at the South Kensington exhibition of 1873, and had begged Vuillaume to sell his prized Stradivari. Vuillaume refused, of course, and the king, by all accounts extremely disappointed, commissioned Vuillaume to make an exact copy in its place. Sadly the original correspondence is lost, but one can imagine Vuillaume’s assurances that the copy would be, at the very least, of the same quality as the Messiah itself!

The violin was seen by Hills in 1940, when it was in the possession of H.S. Braddyll of London, and was in Louis Feiler’s collection by the early 1950s, possibly at the same time as the Caraman de Chimay violin of 1865. After Feiler’s death, it passed via an unknown owner to William Moennig & Son, who sold it to Charles Stein of Baltimore in 1970. Again Stein retained possession until his death, when it was acquired by Ellen Pendleton, who sold it via Moennigs to C.M. Sin in 2000.

Labelled Jean Baptiste Vuillaume à Paris, 3, rue Demours-Ternes, JBV, with the date 1873 inscribed on the label, the violin is numbered 2936.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Feature Type

- Instrument Type

-

Maker

- Albani I, Matthias (2)

- Amati, Andrea (8)

- Amati, Antonio & Girolamo (6)

- Amati, Girolamo II (6)

- Amati, Nicolò (6)

- Balestrieri, Tommaso (3)

- Banks, Benjamin (1)

- Bazin, Charles Nicolas (1)

- Bergonzi Family (1)

- Bergonzi, Carlo (2)

- Bergonzi, Michele Angelo (2)

- Bernardel, Auguste Sébastien Philippe (2)

- Bisiach, Leandro (2)

- Bultitude, Arthur Richard (1)

- Bussetto, Giovanni Maria del (1)

- Camilli, Camillo (2)

- Cappa, Gioffredo (2)

- Carcassi, Lorenzo & Tomaso (1)

- Ceruti, Giovanni Battista (3)

- Chanot, George Adolph (1)

- Cuypers, Johannes Theodorus (1)

- Dalla Costa, Pietro Antonio (1)

- Deconet, Michele (1)

- Fendt, Bernard Simon II (1)

- Fendt, Bernhard Simon I (1)

- Gabrielli, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gagliano, Alessandro (2)

- Gagliano, Ferdinando (1)

- Genova, Giovanni Battista (1)

- Gisalberti, Andrea (1)

- Goffriller, Francesco (1)

- Goffriller, Matteo (1)

- Grancino, Giovanni (4)

- Grancino, Giovanni Battista II (1)

- Guadagnini, Gaetano II (1)

- Guadagnini, Giovanni Battista (7)

- Guarneri 'filius Andreæ', Giuseppe (3)

- Guarneri del Gesù, Giuseppe (5)

- Guarneri of Mantua, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Guarneri of Venice, Pietro (3)

- Guarneri, Andrea (3)

- Götz, Conrad (1)

- Hill & Sons, W.E. (1)

- Kennedy, Thomas (1)

- Knopf, Carl Heinrich (1)

- Landolfi, Carlo Ferdinando (1)

- Lott, John Frederick (1)

- Lupot, Nicolas (2)

- Mantegazza, Pietro Giovanni (2)

- Mariani, Antonio (1)

- Montagnana, Domenico (2)

- Panormo, Vincenzo Trusiano (1)

- Parker, Daniel (1)

- Peccatte, Dominique (1)

- Platner, Michele (1)

- Pressenda, Giovanni Francesco (1)

- Rayman, Jacob (1)

- Retford, William Charles (1)

- Rivolta, Giacomo (1)

- Rocca, Giuseppe Antonio (2)

- Rota, Giovanni (1)

- Rugeri, Francesco (3)

- Sartory, Eugène (1)

- Scarampella, Stefano (2)

- Schwartz, George Frédéric (1)

- Serafin, Santo (1)

- Sgarabotto, Gaetano (1)

- Sgarabotto, Pietro (1)

- Simon, Pierre (1)

- Stainer, Jacob (3)

- Storioni, Lorenzo (3)

- Stradivari, Antonio (14)

- Stradivari, Francesco (1)

- Stradivari, Omobono (1)

- Tadioli, Maurizio (1)

- Taylor, Michael (1)

- Tecchler, David (2)

- Testore, Carlo Giuseppe (1)

- Tourte, François Xavier (4)

- Tubbs, James (1)

- Voller Brothers (1)

- Vuillaume, Jean-Baptiste (10)

- Watson, William (1)

- da Salò Bertolotti, Gasparo (2)

- Author

- Charity

-

In the Press

- Antiques Trade Gazette (3)

- Archi-magazine.it (1)

- Art Daily (2)

- CNN Style (1)

- Classic FM (2)

- ITV (1)

- Ingles & Hayday (4)

- Liberation (1)

- Life Style Journal (1)

- London Evening Standard (1)

- Paul Fraser Collectibles (1)

- Rhinegold Publishing (1)

- Sotheby's (1)

- Strings Magazine (2)

- Tarisio (2)

- The Fine Art Post (1)

- The Strad (7)

- The Times (1)